Python微信订餐小程序课程视频

https://edu.csdn.net/course/detail/36074

Python实战量化交易理财系统

https://edu.csdn.net/course/detail/35475

目录* TypeScript学习第一章:TypeScript初识

- 1.1 TypeScript学习初见

- 1.2 TypeScript介绍

- 1.3 JS 、TS 和 ES之间的关系

- 1.4 TS的竞争者有哪些?

- 2.1 发现问题

- 2.2 静态类型检查

- 2.3 非异常故障

- 2.4 使用工具

- 2.5 优化编译

- 2.6 显式类型

- 2.7 降级编译

- 2.8 严格模式

- 3.1 基元类型string number 和 boolean

- 3.2 数组

- 3.3 any

- 3.4 变量上的类型解释

- 3.5 函数

- 3.6 对象类型

- 3.7 联合类型

- 3.8 类型别名

- 3.9 接口

- 3.10 类型断言 as

- 3.11 文字类型

- 3.12

null和undefined - 3.13 枚举

- 3.14 不太常见的原语

- 4.1

typeof类型守卫 - 4.2 真值缩小

- 4.3 等值缩小

- 4.4

in操作符缩小 - 4.5

instanceof操作符缩小 - 4.6 分配缩小

- 4.7 控制流分析

- 4.8 使用类型谓词

- 4.9 受歧视的

unions - 4.10

never类型与穷尽性检查 - 5.1 函数类型表达式

- 5.2 调用签名: 属性签名

- 5.3 构造签名 new (params, ...): Ctor

- 5.4 泛型函数

- 5.5 可选参数 ?

- 5.6 函数重载: 重载签名

- 5.7 需要了解的其他类型

- 5.8 函数展开运算符

- 5.9 参数解构

- 5.10 函数的可分配性: 返回

void类型 - 6.1 属性修改器

- 6.2 可选属性

- 6.3 只读属性

- 6.4 索引签名

- 6.5 扩展类型

- 6.6 交叉类型

- 6.7 接口与交叉类型

- 6.8 泛型对象类型

- 6.9 数组类型

- 6.10 只读数组类型

- 6.11 元组类型

- 6.12 只读元组类型

- 7.0 从类型中创建类型

- 7.1 泛型

- 7.2

keyOf类型操作符 - 7.3

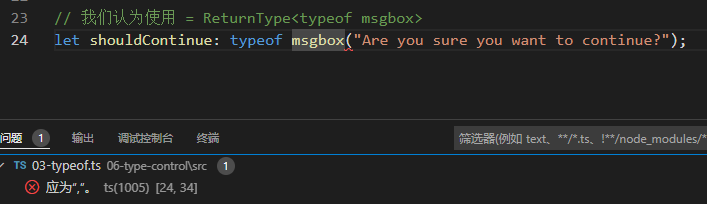

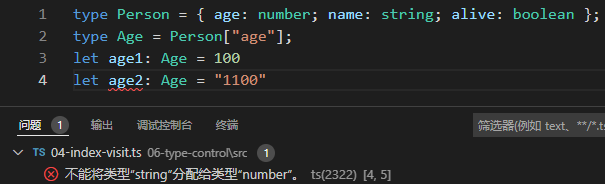

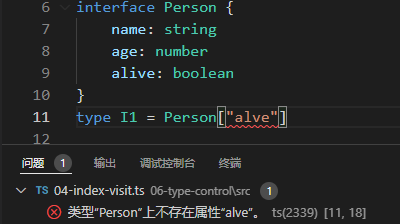

typeof类型操作符 - 7.4 索引访问类型

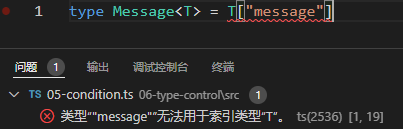

- 7.5 条件类型

- 7.6 映射类型

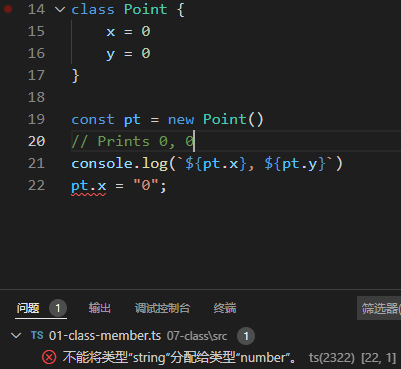

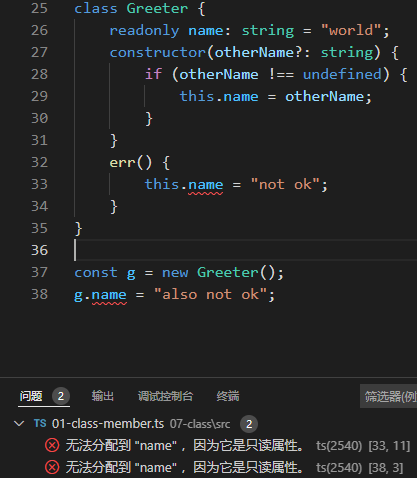

- 8.1 类成员

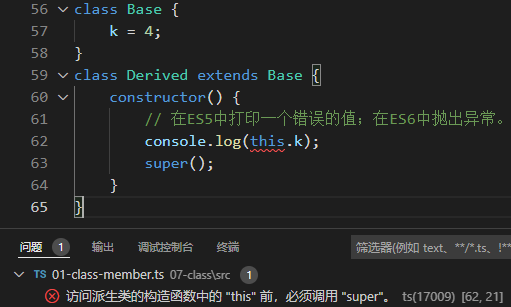

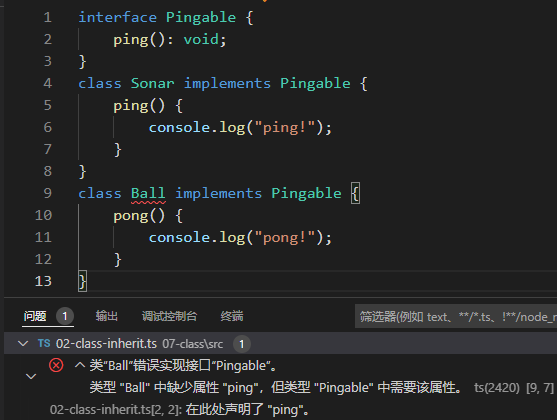

- 8.2 类继承

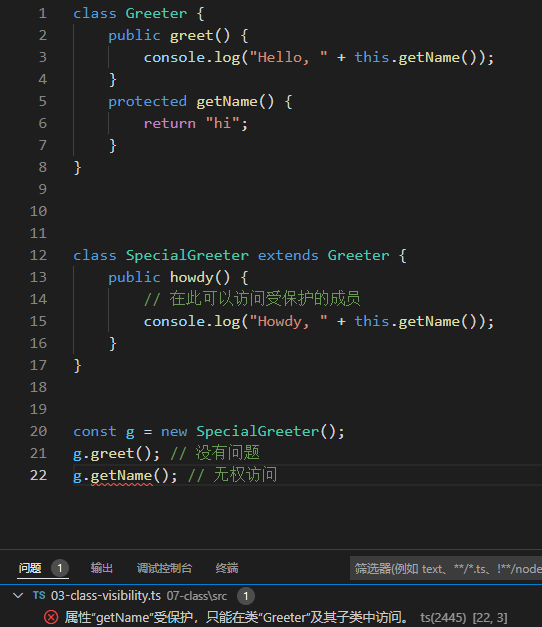

- 8.3 成员的可见性

- 8.4 静态成员

- 8.5 类里的

static区块 - 8.6 泛型类

- 8.7 类运行时的

this - 8.8

this类型 - 8.9 基于类型守卫的

this(???不太会) - 8.10 参数属性,构造函数参数转类属性

- 8.11 类表达式

- 8.12 抽象类和成员

- 8.13 类之间的关系

- 9.1 如何定义JavaScript模块

- 9.2 非模块

- 9.3 TypeScript中的模块

- 9.4 CommonJS 语法

- 9.6 TypeScript的模块输出选项

- 9.7 TypeScript 命名空间

TypeScript学习第一章:TypeScript初识

1.1 TypeScript学习初见

TypeScript(TS)是由微软Microsoft由2012年推出的自由和开源的编程语言, 目前主流的三大框架React 、Vue 和 Angular这三大主流框架再加上最新的鸿蒙3.0都可以用TS进行开发.

可以说 TS 是 JS 的超集, 是建立在JavaScript上的语言. TypeScript把其他语言的一些精妙的语法, 带入到JavaScript中, 让JS达到了一个新的高度。

可以在TS中使用JS以外的扩展语法, 同时可以结局TS对面向对象和静态类型的良好支持, 可以让我们编写更健壮、更可维护的大型项目。

1.2 TypeScript介绍

因为TypeScript是JavaScript的超集, 所以要介绍TS, 不得不提一下JS, JS从在引入编程社区20多年以来, 已经成了有史以来应用最广泛的跨平台语言之一了, 从一开始为网页中添加一些微不足道的、交互性的小型的脚本语言发展到现在各种规模的前端和后端应用程序的首选语言了.

虽然我们用JS语言编写程序的大小、范围和复杂性呈指数级的增长, 但是JS语言表达不同代码单元之间的关系和能力却很弱, 使得JS成了一项难以大规模管理的任务, 而且也很难解决程序员经常出现的错误: 类型错误.

而TS语言可以很好的解决这个错误, 他的目标是成为JS程序的静态类型检查器, 可以在代码运行之前进行检查, 也就是静态编译, 并且呢, 可以确保我们程序的类型正确(即进行类型检查).

TS添加了可选的静态类型和基于类的面向对象编程等等, 是JS的语言扩展, 不是JS的替代品, 会让JS前进的步伐更坚实、更遥远.

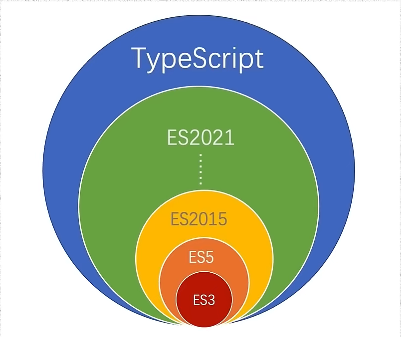

1.3 JS 、TS 和 ES之间的关系

ES6又称为ECMAScript 2015, TypeScript 是 JS 的超集, 他包含Javascript的所有元素, 能运行Javascript代码, 并扩展了JS语法, 并添加了静态类型 类 模块 接口 类型注解等等方面的功能, 更加易于大项目的开发.

这张图表示TS不仅包含了JS和ES的最新内容, 还扩展了新的功能.

总的来说, ECMAScript是JS的标准, TS是JS的超集.

1.4 TS的竞争者有哪些?

1. ESLint

2. TSlint

1 和 2 都是和TypeScript一样来突出代码中可能出现的错误, 至少i没有为检查过程添加新的语法, 但是这两者都不打算最为IDE集成的工具来运行, 这两个的存在可以是TS做更少的检查, 但是这些检查并不适合于所有的代码库。

3. CoffeeScript

CoffeeScript是想改进JS语言, 但是现在用的人少了, 因为他又成为了JS的标准, 属于是打不过JS了。

4.Flow

Vue2的源码的类型检查工具就是flow, 不过Vue3已经开始使用TS做类型检查了.

Flow更悲观的判断类型, 而TS更加乐观.

Flow是为了维护Facebook的代码库而建立的, 而TS是作为一种独立的语言而建立的, 其内部有独立的环境, 可以自由专注于工具的开发和整个生态系统的维护

TypeScript学习第二章:为什么使用TypeScript?

2.1 发现问题

JS中每个值都有一组行为, 我们可以通过运行不同的操作来观察:

| | // 在 'message' 上访问属性方法 'toLowerCase', 并调用它 |

| | message.toLowerCase(); |

| | // 调用 'message' |

| | message(); |

我们尝试直接调用message, 但是假设我们不知道message, 我们就无法可靠的说出尝试运行任何的这些代码会得到什么结果, 每个操作的结果完全取决于我们最初给message的赋值. 我们编译代码的时候真的可以调用message()么, 也不一定有toLowerCase()这个方法, 而且也不知道他们的返回值是什么.

通常我们在编写js的时候需要对上面所述的细节牢记在心, 才能编写正确的代码。

假设我们知道了message 是什么,如下所示,但是第三行就会报错。

| | const message = 'Hello World' |

| | message.toLowerCase(); // 输出hello world |

| | message(); // TypeError: message is not a function |

如果我们能避免这样的错误, 就完美了, 当我们运行我们的代码的时候, 选择做什么的方式, 是通过确定值的类型, 来确定他具有什么样的行为和功能的, TypeError 就暗指字符串是不能作为函数来调用的. 对于某些值, 比如string和number, 我们可以使用typeof来识别他们的类型.

但是对于像函数之类的其他的东西, 没有相应的运行时机制, 比如下面的代码, 运行是有条件的, 也就是说这个x是必须具有flip这个方法的, js只能在运行一下代码时才能知道这个x是提供了什么的, 我们如果能够使用静态类型系统, 在运行代码之前预测预期的代码,问题就解决了.

| | function fn(x) { |

| | return x.flip() |

| | } |

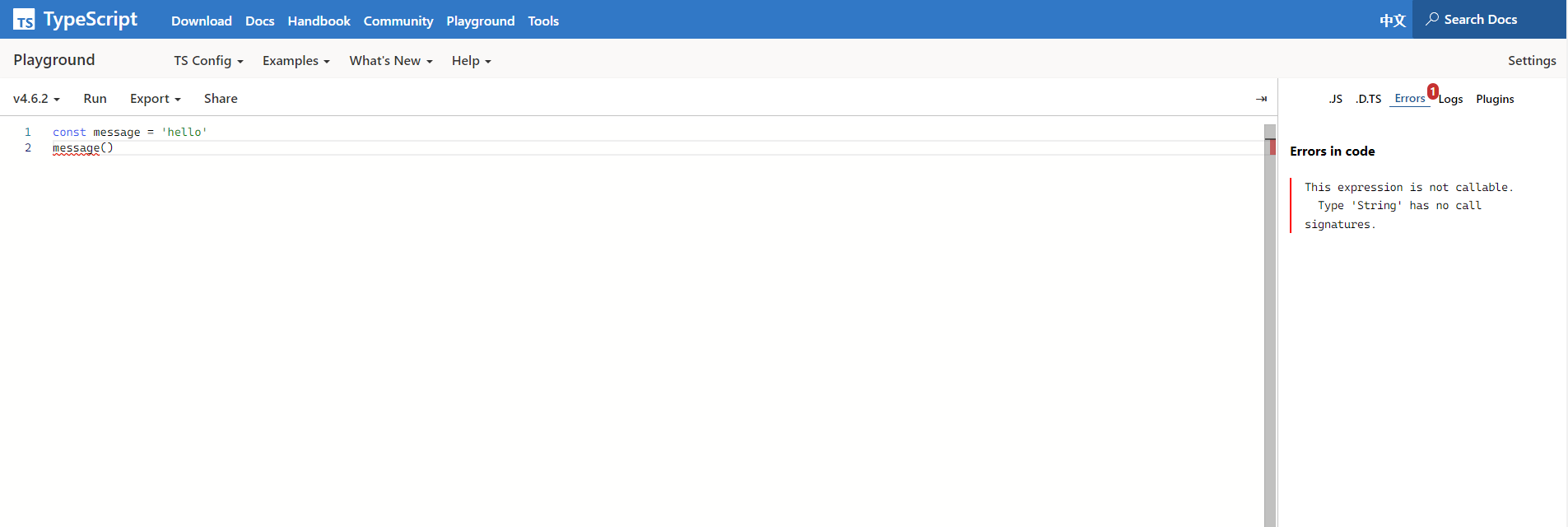

2.2 静态类型检查

| | const message = 'hello' |

| | message() // TypeError |

上述这段代码会引起TypeError, 理想的情况下, 我们希望有一个工具可以在我们代码运行之前发现这些错误, TS就可以实现这些功能. 静态类型系统就描述了当前我们运行程序的时候, 值得形状和行为, 像TS这样的类型检查器, 会告诉我们什么时候代码会出现问题.

2.3 非异常故障

JS 在运行的时候会告诉我们他认为某些东西是没有意义的情况, 因为ECMA规范明确说明了JS在遇到某些意外情况下应该是如何表现得, 比如如下代码:

| | const user = { |

| | name: "小千", |

| | age:26, |

| | }; |

| | |

| | user.location; // 返回undefined, 理应报错, 因为根本没有location这个属性 |

但是静态类型系统要求必须对调用哪些代码做系统的标记, 如果是在TS运行这段代码, 就会出现location未定义的错误, 如下图所示:

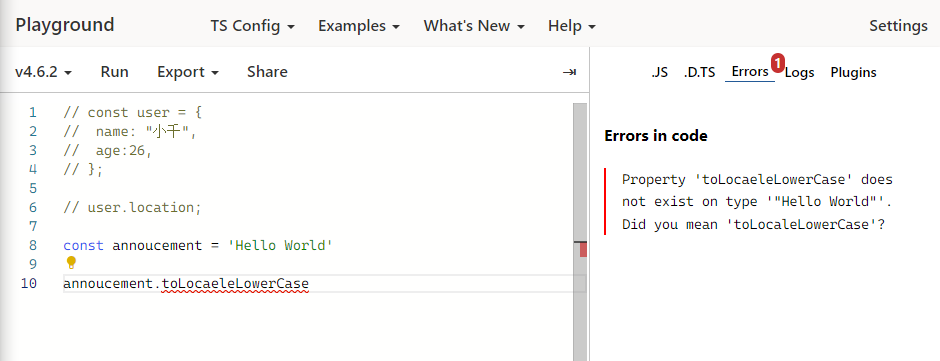

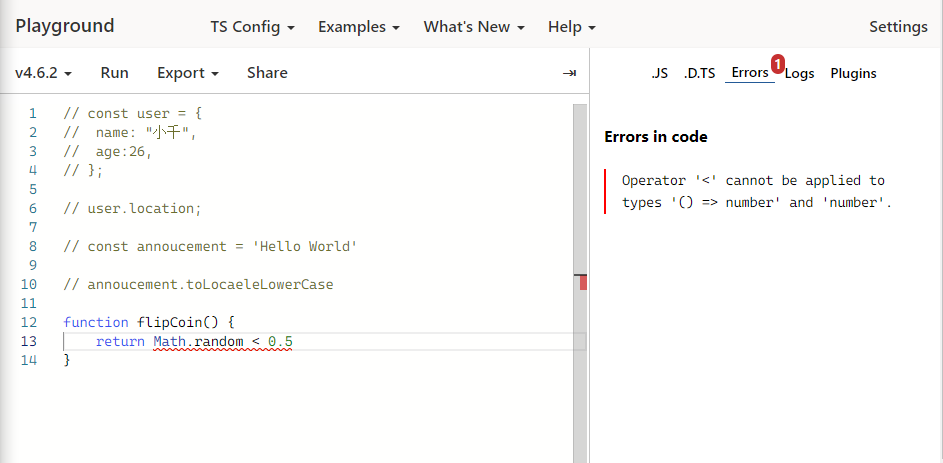

TS可以在开发过程中捕获很多类似于合法的错误, 比如说错别字, 未调用函数, 基本的逻辑错误等等:

拼写错误: 属性toLocaeleLowerCase在String类型中不存在, 你找的是否是toLocaleLowerCase属性?

未调用的函数检查: 运算符号 < 不能用在一个 '() => number' 和 number数字之间.

逻辑问题: value !== 'a' 和 value === 'b'逻辑重叠.

2.4 使用工具

- 安装VSCode

- 安装Node.js:使用命令

node -v来检查nodejs版本 - 安装TypeScript编译器:

npm i typescript -g

然后我们要编译我们的TS, 因为TS是不能直接运行的, 我们必须把他编译成JS.

在终端中使用cls 或者 clear命令可以清屏

可以使用tsc命令来转换TS 成 JS: 例如 tsc hello.ts, 就会生成对应的JS文件.

hello.ts:

| | // 你好, 世界 |

| | // console.log('Hello World') |

| | |

| | // 会出现函数实现重复的错误 |

| | function greet(person, date) { |

| | console.log(`Helo ${person}, today is ${date}`) |

| | } |

| | |

| | greet('xiaoqian','2021/12/04') |

| | |

会出现函数实现重复的错误是因为hello.js也有这个greet的函数, 这是跟我们编译环境是矛盾的, 而且还需要我们重新编译ts, 所以我们需要进行优化编译过程.

2.5 优化编译

- 解决TS和JS冲突问题

tsc --init # 生成配置文件 - 自动编译

tsc --watch - 发出错误

tsc --noEmitOnError hello.ts

TS文件编译成JS文件以后, 当出现函数名或者是变量名相同的时候, 会给我们提示重复定义的问题,可以通过 tsc --init来生成一个配置文件来解决冲突问题. 先把严格模式strict关闭, 可解决未指定变量类型的问题.

当我们修改TS文件的时候, 我们需要重新的执行编译, 才能拿到最新的结果我们需要自动编译, 可以通过tsc --watch 来解决自动编译的问题.

当我们编译完之后, JS还是能正常运行的, 我们可以加一个noEmitOnError的参数来解决, 这样的话如果我们在TS中出现错误就可以让TS不编译成JS文件了.

最终的命令行指令是这样的:

| | tsc --watch --noEmitOnError |

2.6 显式类型

刚才我们在tsconfig.json里把strict模式关闭了, 如果我们打开, 就会出现未指定变量类型的错误, 如果要解决这个问题, 我们就需要指定显式类型:

什么叫显式类型呢, 就是手工的给变量定义类型, 语法如下:

| | function greet(person: string, date: Date) { |

| | console.log(`Helo ${person}, today is ${date.toDateString()}.`) |

| | } |

在TS中, 也不是必须指定变量的数据类型, TS会根据你的变量自动推断数据类型, 如果推断不出来就会报错.

2.7 降级编译

我们可以在tsconfig.json 就修改target来更改TS编译目标的代码版本.

| | { |

| | "compilerOptions": { |

| | ...... |

| | "target": 'es5', |

| | ...... |

| | } |

| | } |

默认为es2016, 即es7, 建议以默认值就可以, 目前的浏览器都能兼容

2.8 严格模式

不同的用户使用TS在类型检查中希望检查的严格程度是不同的, 有的人喜欢更宽松的验证体验, 从而仅仅验证程序的某些部分, 并且仍然拥有不错的工具.

默认情况下:

| | { |

| | "compilerOptions": { |

| | ......, |

| | "strict": true, /* 严格模式: 启用所有严格的类型检查选项。*/ |

| | "noImplicitAny": true, /* 为隐含的'any'类型的表达式和声明启用错误报告。*/ |

| | "strictNullChecks": true, /* 当类型检查时,要考虑'null'和'undefined' */ |

| | ...... |

| | } |

| | } |

一般来说使用TS就是追求的强立即验证, 这些静态检查设置的越严格, 越可能需要更多额外的编程工作, 但是从长远来说是值得的, 它会使代码更加容易维护. 如果可以我们应该始终打开这些类型检查.

启用strictNullChecks可以拦截null 和undefined 的错误, 启用noImplicitAny可以拦截any的错误, 启用strict可以拦截所有的严格类型检查选项, 包括前面两个的.

所以结论就是只需要开启"strict"为true即可, 当我们遇到

TypeScript学习第三章: 常用类型

3.1 基元类型string number 和 boolean

- string: 字符串, 例子: 'Hello', 'World'.

- number: 数字, 例子: 42, -100.

- boolean: 布尔, 例子: true, false.

String Number Boolean 也是合法的, 在TS里专门指一些很少的, 出现在代码里的一些特殊的内置类型, 对于类型我们始终使用小写的string, number 和 boolean.

为了输出方便我们可以在tsconfig.json的rootDir里设置一个目录"./src", 设置outDir为"./dist".

| | let str: string = 'hello typescript' |

| | let num: number = 100 |

| | let bool: boolean = true |

3.2 数组

数组的定义方法有两种:

- type[]

- Array

Array这种方法又称为泛型, 其中type是任意合法的类型.

| | let arr: number[] = [1, 4, 6 ,8] |

| | // arr = ['a'] |

| | let arr2: Array<number> = [1, 2, 3] |

| | arr2 = [] |

值得注意的是, 数组可以被赋值为空数组[], 但是不能被赋值为规定类型以外的数组值.

3.3 any

如果不希望某个特定值导致类型检查错误, 就可以使用any.

当一个值是any的时候, 可以访问它的任何属性, 将它分配给任何类型的值, 或者几乎任何其它语法上的东西都是合法的. 但是运行的时候该报错还是报错, 所以我们不应该经常使用他.

| | let obj: any = { |

| | x: 0 |

| | } |

| | |

| | obj.foo() // js调用时就会报错 |

| | obj() |

| | obj.bar = 100 |

| | obj = 'hello' |

| | const n: number = obj |

3.4 变量上的类型解释

| | let myName: string = "Felixlu" |

采用(冒号:) + (类型string)的方式.

| | let my: string = "Hello World" |

| | // 如果不声明, 会自动推断 |

| | let myName = "Bleak" // 将myName推断成string |

| | myName = 100 // 报错, 不能将number分配给string. |

3.5 函数

| | function greet (name: string): void { |

| | console.log("Hello," + name.toUpperCase() + "!!!") |

| | } |

| | |

| | const greet2 = (name: string): string =>{ |

| | return "你好," + name |

| | } |

| | |

| | greet("Bleak") |

| | console.log(greet2("黯淡")) |

第一个name: string是参数类型注释, 第二个: void是返回值类型注释.

一般来说不用定义返回值类型, 因为会自动推断.

| | const names = ["xiaoqian", 'xiaoha', 'xiaoxi'] |

| | names.forEach(function(s) { |

| | console.log(s.toUpperCase()); |

| | }) |

| | |

| | names.forEach(s => { |

| | console.log(s.toLowerCase()); |

| | }) |

匿名函数与函数声明有点不同, 当一个函数出现在出现在TS可以确定它如何被调用的地方的时候, 这个函数的参数会自动的指定类型.

3.6 对象类型

| | function printCoord(pt: {x: number; y: number}) { |

| | console.log("坐标的x值是: " + pt.x) |

| | console.log("坐标的y值是: " + pt.y) |

| | } |

| | |

| | printCoord({x: 3, y: 7}) |

对于参数类型注释是对象类型的, 对象中属性的分割可以用 分号; 或者 逗号,

| | function printName(obj: {first: string, last?: string}) { |

| | if(obj.last === undefined) { |

| | console.log("名字是:" + obj.first) |

| | } else { |

| | console.log("名字是:" + obj.first + obj.last) |

| | } |

| | |

| | } |

| | |

| | printName({ |

| | first: "Mr.", |

| | last: "Bleak" |

| | }) |

使用?可以指定对象中某个参数可以选择传入或者不传入, 不传入其值就是undefined.

如何在函数体内确定某个带?的参数是否传参了呢?可以使用两种方法

| if(obj.last === undefined) {// 未传入时的方法体 | |

|---|---|

| } else {// 传入时的方法体 | |

| } |

2. ```

| | console.log(obj.last?.toUpperCase()) |

第二种方式更加优雅, 更推荐使用

3.7 联合类型

| | let id: number | string |

TS的类型系统允许我们使用多种运算符, 从现有类型中构建新类型union.

联合类型是由两个或多个其他类型组成的类型. 表示可能是这些类型中的任何一种的值, 这些类型中的每一种被称为联合类型的成员.

| | function printId(id: number | string) { |

| | console.log("当前Id为:" + id) |

| | // console.log(id.toUpperCase()) |

| | if (typeof id === 'string') { |

| | console.log(id.toUpperCase()) |

| | } else { |

| | console.log(id) |

| | } |

| | } |

| | |

| | printId(101) |

| | printId('202') |

如果需要调用一些参数的属性或者方法, 可以使用JS携带的typeof函数来进行判断并分情况执行代码.

| | function welcomePeople(x: string[] | string) { |

| | if(Array.isArray(x)) { // Array.isArray(x)可以测试x是否是一个数组 |

| | console.log("Hello, " + x.join(' and ')) |

| | } else { |

| | console.log("Welcome lone traveler " + x) |

| | } |

| | } |

| | |

| | |

| | welcomePeople(["A", "B"]) |

| | welcomePeople('A') |

根据分支来进行操作的函数.

| | // 共享的方法 |

| | function getFirstThree(x: number[] | string) { |

| | return x.slice(0, 3) |

| | } |

都有的属性和方法, 可以直接使用.

3.8 类型别名

| | type Point = { |

| | x: number |

| | y: number |

| | } // 对象类型 |

| | function printCoord(pt: Point) { |

| | |

| | } |

| | printCoord({x: 100, y: 200}) |

| | |

| | |

| | type ID = number | string // 联合类型 |

| | function printId(id: ID) { |

| | |

| | } |

| | |

| | printId(100) |

| | printId('2333') |

| | |

| | type UserInputSanitizedString = string // 基元类型 |

| | function sanitizedString(str: string): UserInputSanitizedString { |

| | return str.slice(0, 2) |

| | } |

| | |

| | let userInput = sanitizedString('hello') |

| | console.log(userInput) |

type可以用来定义变量的类型, 如果是对象, 里面的属性和方法可以用逗号, 分号; 或直接不写来做间隔, 可以用来做一些平时经常会用到的类型来做复用, 其可以用于变量的类型指定上.

3.9 接口

| | interface Point { |

| | x: number; |

| | y: number; |

| | } |

| | |

| | function printCoord(pt: Point) { |

| | console.log("坐标x的值是: " + pt.x) |

| | console.log("坐标y的值是: " + pt.y); |

| | } |

| | printCoord({ x: 100, y: 100 }) |

| | |

可以用接口来定义对象的类型, 几乎所有可以通过interface来定义的类型都可以用type来定义

类型别名type 和接口interface之间的区别:

- 扩展接口: 通过extends

| | // 扩展接口 |

| | interface Animal { |

| | name: string |

| | } |

| | |

| | interface Bear extends Animal { |

| | honey: boolean |

| | } |

| | |

| | const bear: Bear = { |

| | name: 'winie', |

| | honey: true |

| | } |

| | |

| | console.log(bear.name, bear.honey) |

扩展类型别名: 通过 &

| | type Animal = { |

| | name: string |

| | } |

| | |

| | type Bear = Animal & { |

| | honey: boolean |

| | } |

| | |

| | const bear: Bear = { |

| | name: "winie", |

| | honey: true |

| | } |

- 向现有的类型添加新字段

接口: 定义相同的接口, 其字段会合并.

| | interface MyWindow { |

| | count: number |

| | } |

| | |

| | interface MyWindow { |

| | title: string |

| | } |

| | |

| | const w: MyWindow = { |

| | title: 'hello ts', |

| | count: 10 |

| | } |

类型别名: 类型别名创建的类型创建后是不能添加新字段的

3.10 类型断言 as

| | const myCanvas = document.getElementById("main\_canvas") // 返回某种类型的HTMLElement |

| | |

| | // 可以使用类型断言来指定 |

| | const myCanvas = document.getElementById("main\_canvas") as HTMLCanvasElement |

| | const myCanvas = <HTMLCanvasElement>document.getElementById() |

类型注释与类型断言一样, 类型断言由编译器来删除, 不会影响代码的运行时行为, 也就是因为类型断言在编译时被删除, 所以没有与类型断言相关联的运行时检查.

| | const x = ('hello' as unknown) as number |

如上代码可以在我们不知道某些代码是什么类型的时候断言为一个差不多的类型.

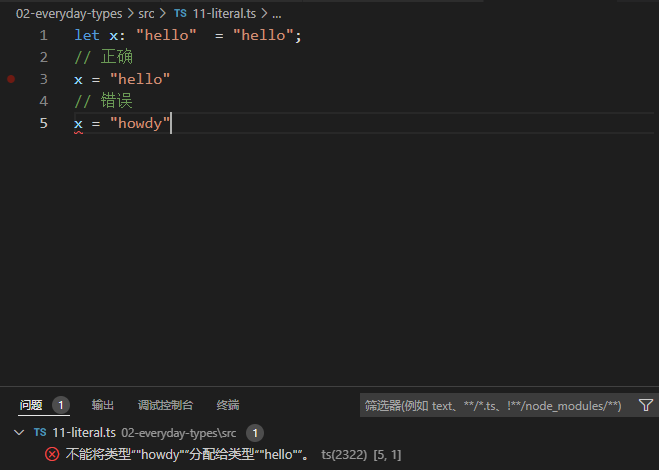

3.11 文字类型

除了一般类型string 和number, 还可以在类型位置引用特定的字符串和数字.

一种方法是考虑js如何以不同的方式声明变量. var和let两者都允许更改变量中保存的内容, const不允许, 这反映在TS如何为文字创建类型上

| | let testString = "Hello World"; |

| | testString = "Olá Mundo"; |

| | |

| | // 'testString'可以表示任何可能的字符串,那TypeScript是如何在类型系统中描述它的 |

| | testString; |

| | const constantString = "Hello World"; |

| | // 因为'constantString'只能表示1个可能的字符串,所以具有文本类型表示 |

| | constantString; |

就其本身而言, 文字类型不是很有价值

| | let x: "hello" = "hello"; |

| | // 正确 |

| | x = "hello" |

| | // 错误 |

| | x = "howdy" |

拥有一个只能由一个值的变量并没有多大用处!

但是通过将文字组合成联合,你可以表达一个更有用的概念——例如,只接受一组特定已知值的函数:

| | function printText(s: string, alignment: "left" | "right" | "center") { |

| | // ... |

| | } |

| | printText("Hello, world", "left"); |

| | printText("G'day, mate", "centre"); |

数字文字类型的工作方式相同:

| | function compare(a: string, b: string): -1 | 0 | 1 { |

| | return a === b ? 0 : a > b ? 1 : -1; |

| | } |

也可以将这些与非文字类型结合使用:

| | interface Options { |

| | width: number; |

| | } |

| | function configure(x: Options | "auto") { |

| | // ... |

| | } |

| | configure({ width: 100 }); |

| | configure("auto"); |

| | configure("automatic"); |

还有一种文字类型:布尔文字。只有两种布尔文字类型,它们是类型 true 和 false 。类型 boolean 本身实际上只是联合类型 union 的别名 true | false 。

文字推理

当你使用对象初始化变量时,TypeScript 假定该对象的属性稍后可能会更改值。例如,如果你写了这样的代码:

| | const obj = { counter: 0}; |

| | if(someCondtion) { |

| | obj.counter = 1 |

| | } |

TypeScript 不假定先前具有的字段值 0 ,后又分配 1 是错误的。另一种说法是 obj.counter 必须有 number 属性, 而非是 0 ,因为类型用于确定读取和写入行为。

这同样适合用于字符串:

| | function handleRequest(url: string, method: 'GET' | 'POST' | 'GUESS') { |

| | // ... |

| | } |

| | const req = { url: 'https://example.com', method: 'GET' }; |

| | handleRequest(req.url, req.method); |

在上面的例子 req.method 中推断是 string ,不是 "GET" 。因为代码可以在创建 req 和调用之间进行评估,TypeScript 认为这段代码有错误。

有两种方法可以解决这个问题:

- 可以通过在任一位置添加类型断言来更改推理:

| | // 方案 1: |

| | const req = { url: "https://example.com", method: "GET" as "GET" }; |

| | // 方案 2 |

| | handleRequest(req.url, req.method as "GET"); |

方案1表示“我打算 req.method 始终拥有文字类型"GET" ”,从而防止之后可能分配"GUESS"给该字段。

方案 2 的意思是“我知道其他原因req.method具有"GET"值”。

- 可以使用

as const将整个对象转换为类型文字

| | const req = { url: "https://example.com", method: "GET" } as const; |

| | handleRequest(req.url, req.method); |

该as const后缀就像const定义,确保所有属性分配的文本类型,而不是一个更一般的string或 number 。

3.12 null和undefined

JavaScript 有两个原始值用于表示不存在或未初始化的值: null 和 undefined.

TypeScript有两个对应的同名类型。这些类型的行为取决于您是否在tsconfig.json设置strictNullChecks选择。

strictNullChecks关闭

使用false,仍然可以正常访问的值,并且可以将值分配给任何类型的属性。这类似于没有空检查的语言 (例如 C#、Java)的行为方式。缺乏对这些值的检查往往是错误的主要来源;如果在他们的代码库中这样做可行,我们总是建议大家打开。

strictNullChecks开启

使用true,你需要在对该值使用方法或属性之前测试这些值。就像在使用可选属性之前检查一样,我们可以使用缩小来检查可能的值:

| | function doSomething(x: string | null) { |

| | if (x === null) { |

| | // 做一些事 |

| | } else { |

| | console.log("Hello, " + x.toUpperCase()); |

| | } |

| | } |

- 非空断言运算符(

!后缀)

TypeScript 也有一种特殊的语法 null , undefined , 可以在不进行任何显式检查的情况下,从类型中移除和移除类型。 ! 在任何表达式之后写入实际上是一种类型断言,即该值不是 null or undefined :

使用?可以指定对象中某个参数可以选择传入或者不传入, 不传入其值就是undefined.

| | function liveDangerously(x?: number | null) { |

| | // 正确 |

| | console.log(x!.toFixed()); |

| | } |

就像其他类型断言一样,这不会更改代码的运行时行为,因此仅 ! 当你知道该值不能是 null 或 undefined 时使用才是重要的。

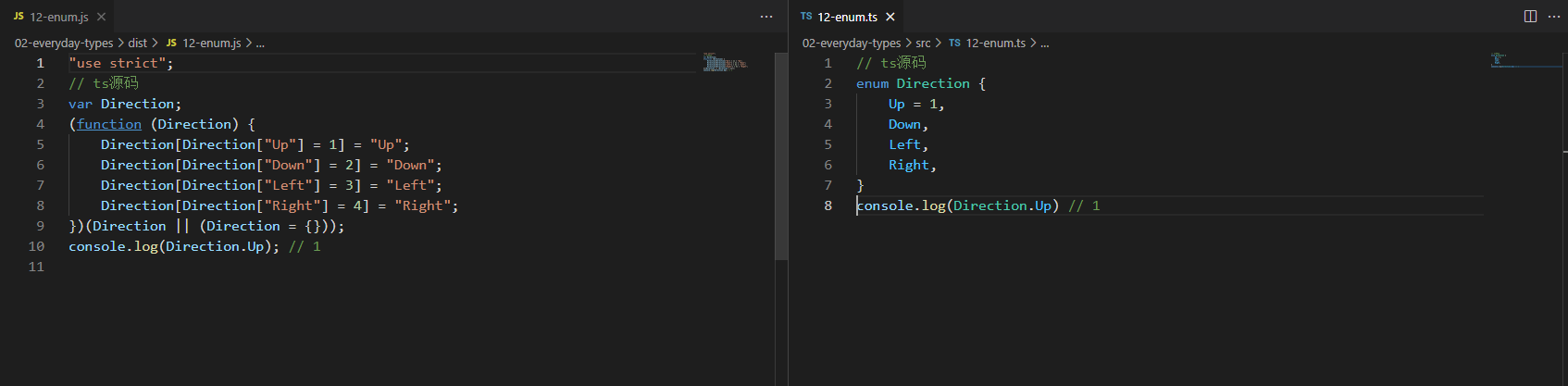

3.13 枚举

枚举是 TypeScript 添加到 JavaScript 的一项功能,它允许描述一个值,该值可能是一组可能的命名常量之一。与大多数 TypeScript 功能不同,这不是JavaScript 的类型级别的添加,而是添加到语言和运行时的内容。因此,你确定你确实需要枚举在做些事情,否则请不要使用。可以在Enum参考页中阅读有关枚举的更多信息。

| | // ts源码 |

| | enum Direction { |

| | Up = 1, |

| | Down, |

| | Left, |

| | Right, |

| | } |

| | console.log(Direction.Up) // 1 |

| | // 编译后的js代码 |

| | "use strict"; |

| | var Direction; |

| | (function (Direction) { |

| | Direction[Direction["Up"] = 1] = "Up"; |

| | Direction[Direction["Down"] = 2] = "Down"; |

| | Direction[Direction["Left"] = 3] = "Left"; |

| | Direction[Direction["Right"] = 4] = "Right"; |

| | })(Direction || (Direction = {})); |

| | console.log(Direction.Up); |

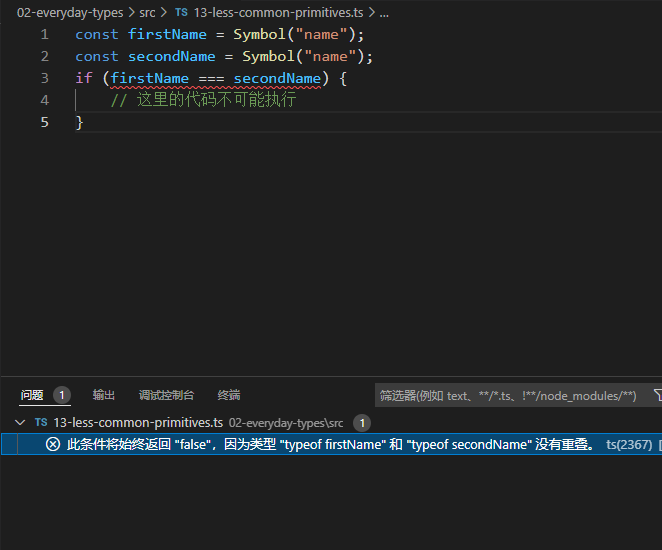

3.14 不太常见的原语

值得一提的是JavaScript中一些较新的原语, 它们在 TypeScript 类型系统中也实现了。我们先简单的看两个例子:

bigint

从 ES2020(ES11) 开始,JavaScript 中有一个用于非常大的整数的原语BigInt :

| | // 通过bigint函数创建bigint |

| | const oneHundred: bigint = BigInt(100); |

| | // 通过文本语法创建BigInt |

| | const anotherHundred: bigint = 100n; |

你可以在TypeScript 3.2发行说明中了解有关 BigInt 的更多信息。

symbol

JavaScript 中有一个原语 Symbol() ,用于通过函数创建全局唯一引用:

| | const firstName = Symbol("name"); |

| | const secondName = Symbol("name"); |

| | if (firstName === secondName) { |

| | // 这里的代码不可能执行 |

| | } |

此条件将始终返回 false ,因为类型typeof firstName和typeof secondName没有重叠。

TypeScript学习第四章: 类型缩小

假设我们有一个名为padLeft的函数:

| | function padLeft(padding: number | string, input: string): string { |

| | throw new Error("尚未实现!"); |

| | } |

我们来扩充一下功能: 如果padding是number, 它会将其视为我们将要添加到input的空格数; 如果padding是string, 它只在input上做padding. 让我们尝试实现:

| | function padLeft(padding: number | string, input: string): string { |

| | return new Array(padding + 1).join(" ") + input; |

| | } |

这样的话, 我们在padding + 1处会遇到错误. TS警告我们, 运算符+不能应用于类型number | string 和 string, 这个逻辑是对的, 因为我们没有明确检查padding是否为number, 也没有处理它是string的情况, 所以我们我们这样做:

| | function padLeft(padding: number | string, input: string): string { |

| | if (typeof padding === "number") { |

| | return new Array(padding + 1).join(" ") + input; |

| | } |

| | return padding + input; |

| | |

| | } |

如果这大部分看起来像无趣的JavaScript代码,这也算是重点吧。除了我们设置的注解之外,这段 TypeScript代码看起来就像JavaScript。

我们的想法是,TypeScript的类型系统旨在使编写典型的 JavaScript代码变得尽可能容易,而不需要弯腰去获得类型安全。

虽然看起来不多,但实际上有很多价值在这里。就像TypeScript使用静态类型分析运行时的值一样,它在JavaScript的运行时控制流构造上叠加了类型分析,如if/else、条件三元组、循环、真实性检查等,这些都会影响到这些类型。

在我们的if检查中,TypeScript看到typeof padding ==="number",并将其理解为一种特殊形式的代码,称为类型保护。TypeScript遵循我们的程序可能采取的执行路径,以分析一个值在特定位置的最具体的可能类型。它查看这些特殊的检查(称为类型防护)和赋值,将类型细化为比声明的更具体的类型的过程被称为类型缩小。在许多编辑器中,我们可以观察这些类型的变化,我们甚至会在我们的例子中这样做。

TypeScript 可以理解几种不同的缩小结构.

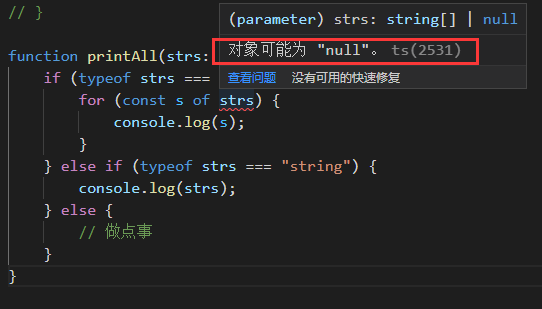

4.1 typeof类型守卫

正如我们所见, Js支持typeof运算符, 它可以提供有关我们在运行时拥有的值类型的非常基本的信息.

TS期望它返回一组特定的字符串:

"string""number""bigint""boolean""symbol""undefined""object""function"

就像我们刚才在padLeft中看到的那样, 这个运算符经常出现在许多JavaScript库中, TS可以理解为, 它缩小在不同分支中的类型.

在TS中, 检查typeof的返回值是一种类型保护. 因为TS对typeof操作进行编码, 从而返回不同的值, 所以它知道对JS做了什么. 例如, 请注意上面的列表中, typeof 不返回null.

| | function printAll(strs: string | string[] | null) { |

| | if (typeof strs === "object") { |

| | for (const s of strs) { |

| | console.log(s); |

| | } |

| | } else if (typeof strs === "string") { |

| | console.log(strs); |

| | } else { |

| | // 做点事 |

| | } |

| | } |

在 printAll 函数中,我们尝试检查 strs 是否为对象,来代替检查它是否为数组类型(现在可能是强调数组是 JavaScript 中的对象类型的好时机)。但事实证明,在 JavaScript 中, typeof null 实际上也是 "object" ! 这是历史上的不幸事故之一。

有足够经验的用户可能不会感到惊讶,但并不是每个人都在 JavaScript 中遇到过这种情况;幸运的是, ts 让我们知道, strs 只缩小到 string[] | null ,而不仅仅是 string[].

这可能是我们所谓的“真实性”检查的一个很好的过渡。

4.2 真值缩小

真值检查是我们在JS中经常做的一件事. 在JS中, 我们可以在条件 && || if语句布尔否定(!)等中使用任何表达式.

例如, if语句不希望它们的条件总是具有类型boolean

| | function getUserOnlineMessage(numUserOnline: number) { |

| | if(numUserOnline) { |

| | return `现在共有 ${numUserOnline} 人在线!` |

| | } |

| | return "现在没有人在线:(" |

| | } |

在JS总, if条件语句, 首先把他们的条件强制转化为boolean以使其有意义, 然后根据结果是true还是false来选择他们的分支. 像下面这些值都强制转换为false:

- 0

- NaN

- "" (空字符串)

- On (bigint 0的版本)

- null

- undefined

其他值被强制转化为true. 你始终可以在Boolean函数中运行值获得boolean, 或使用较短的双布尔否定将值强制转换为boolean.(后者的优点是ts推断出一个狭窄的文字布尔类型true, 而将第一个推断为boolean类型)

| | // 这两个结果都返回 true |

| | Boolean("hello"); // type: boolean, value: true |

| | !!"world"; // type: true, value: true |

利用这个特性, 我们可以防范诸如null或undefined之类的值时. 例如, 让我们尝试将它用于我们的printAll函数.

| | function printAll(strs: string | string[] | null) { |

| | if (strs && typeof strs === "object") { |

| | for (const s of strs) { |

| | console.log(s); |

| | } |

| | } else if (typeof strs === "string") { |

| | console.log(strs); |

| | } |

| | } |

我们通过检查strs是否为真, 消除了上述错误. 这可以防止我们在运行代码的时候出现一些错误, 例如:

| | TypeError: null is not iterable |

但请记住, 对原语的真值检查通常容易出错. 例如, 考虑改写printAll:

| | function printAll(strs: string | string[] | null) { |

| | // !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! |

| | // 别这样! |

| | // 原因在下边 |

| | // !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! |

| | if (strs) { |

| | if (typeof strs === "object") { |

| | for (const s of strs) { |

| | console.log(s); |

| | } |

| | } else if (typeof strs === "string") { |

| | console.log(strs); |

| | } |

| | } |

| | } |

我们将整个函数体包裹在一个真值检查中, 但是这有一个小小的缺点: 我们可能不再正确处理空字符串的情况.

TS在这里根本不会报错, 如果你不熟悉JS, 这是值得注意的. TS通常可以帮你及早发现错误, 但是如果你选择对某个值不做任何处理, 那么它可以做的就只有这么多, 而不会考虑过多逻辑方面的问题, 如果需要, 你可以确保linter(程序规范性)处理此类情况.

关于通过真实性缩小范围的最后一点,是通过布尔否定 ! 把逻辑从否定分支中过滤掉。

| | function multiplyAll( |

| | values: number[] | undefined, |

| | factor: number |

| | ): number[] | undefined { |

| | if (!values) { |

| | return values; |

| | } else { |

| | return values.map((x) => x * factor); |

| | } |

| | } |

4.3 等值缩小

ts也使用分支语句做=== !== ==和 != 等值检查, 来实现类型缩小. 例如:

| | function example(x: string | number, y: string | boolean) { |

| | if (x === y) { |

| | // 现在可以在x,y上调用字符串类型的方法了 |

| | x.toUpperCase(); |

| | y.toLowerCase(); |

| | } else { |

| | console.log(x); |

| | console.log(y); |

| | } |

| | } |

当我们在上面的示例中检查 x 和 y 是否相等时,TypeScript知道它们的类型也必须相等。由于 string 是 x 和 y 都可以采用的唯一常见类型,因此TypeScript 知道 x 、 y 如果都是 string ,则程序走第一个分支中 。

检查特定的字面量值(而不是变量)也有效。在我们关于真值缩小的部分中,我们编写了一个 printAll 容易出错的函数,因为它没有正确处理空字符串。相反,我们可以做一个特定的检查来阻止 null ,并且 TypeScript 仍然正确地从 strs 里移除 null 。

| | function printAll(strs: string | string[] | null) { |

| | if (strs !== null) { |

| | if (typeof strs === "object") { |

| | for (const s of strs) { |

| | console.log(s); |

| | } |

| | } else if (typeof strs === "string") { |

| | console.log(strs); |

| | } |

| | } |

| | } |

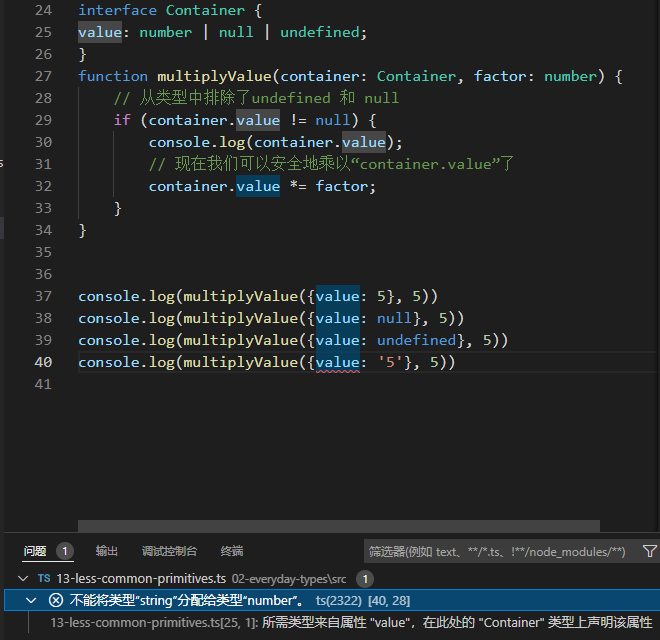

JavaScript 更宽松的相等性检查 == 和 != ,也能被正确缩小。如果你不熟悉,如何检查某个变量是否 == null ,因为有时不仅要检查它是否是特定的值 null ,还要检查它是否可能是 undefined 。这同样适用 于 == undefined :它检查一个值是否为 null 或 undefined 。现在你只需要这个 == 和 != 就可以搞定了。

| | interface Container { |

| | value: number | null | undefined; |

| | } |

| | function multiplyValue(container: Container, factor: number) { |

| | // 从类型中排除了undefined 和 null |

| | if (container.value != null) { |

| | console.log(container.value); |

| | // 现在我们可以安全地乘以“container.value”了 |

| | container.value *= factor; |

| | } |

| | } |

| | |

| | |

| | console.log(multiplyValue({value: 5}, 5)) |

| | console.log(multiplyValue({value: null}, 5)) |

| | console.log(multiplyValue({value: undefined}, 5)) |

| | console.log(multiplyValue({value: '5'}, 5)) |

4.4 in操作符缩小

JavaScript 有一个运算符,用于确定对象是否具有某个名称的属性: in 运算符。TypeScript 考虑到了这 一点,以此来缩小潜在类型的范围。 例如,使用代码: "value" in x 。这里的 "value" 是字符串string, x 是联合类型。值为“true”的分支缩小,需要 x 具有可选或必需属性的类型的值;值为 “false” 的分支缩小,需要具有可选或缺失属性的类型的值。

| | type Fish = { swim: () => void }; |

| | type Bird = { fly: () => void }; |

| | function move(animal: Fish | Bird) { |

| | if ("swim" in animal) { |

| | return animal.swim(); |

| | } |

| | return animal.fly(); |

| | } |

另外,可选属性还将存在于缩小的两侧,例如,人类可以游泳和飞行(使用正确的设备),因此应该出 现在 in 检查的两侧:

| | type Fish = { swim: () => void }; |

| | type Bird = { fly: () => void }; |

| | type Human = { swim?: () => void; fly?: () => void }; |

| | |

| | function move(animal: Fish | Bird | Human) { |

| | if ("swim" in animal) { |

| | // animal: Fish | Human |

| | animal; |

| | } else { |

| | // animal: Bird | Human |

| | animal; |

| | } |

| | } |

4.5 instanceof操作符缩小

JS有一个运算符instanceof检查一个值是否是另一个值的“实例”。更具体地,在JavaScript 中 x instanceof Foo 检查 x 的原型链是否含有 Foo.prototype 。虽然我们不会在这里深入探讨,当 我们进入 类(class) 学习时,你会看到更多这样的内容,它们大多数可以使用 new 关键字实例化。 正如你可能已经猜到的那样, instanceof 也是一个类型保护,TypeScript 在由 instanceof 保护的分支中实现缩小。

| | function logValue(x: Date | string) { |

| | if (x instanceof Date) { |

| | console.log(x.toUTCString()); |

| | } else { |

| | console.log(x.toUpperCase()); |

| | } |

| | } |

| | logValue(new Date()) // Mon, 15 Nov 2021 22:34:37 GMT |

| | logValue('hello ts') // HELLO TS |

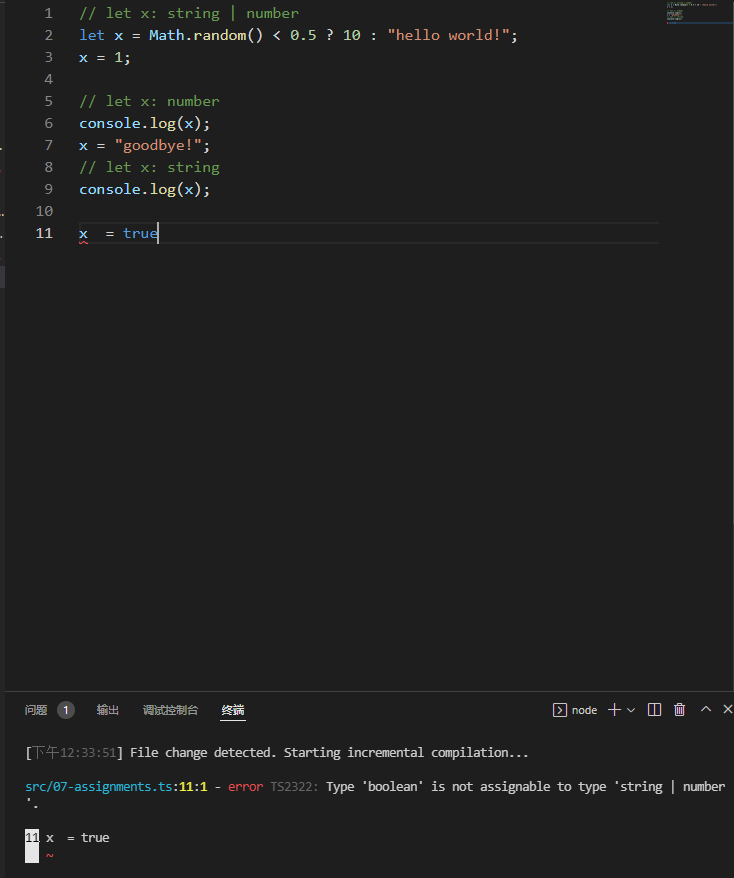

4.6 分配缩小

正如我们之前所提到的, 当我们为任何变量赋值时, TS会检查赋值的右侧并适当缩小左侧.

| | // let x: string | number |

| | let x = Math.random() < 0.5 ? 10 : "hello world!"; |

| | x = 1; |

| | |

| | // let x: number |

| | console.log(x); |

| | x = "goodbye!"; |

| | // let x: string |

| | console.log(x); |

请注意,这些分配中的每一个都是有效的。即使在我们第一次赋值后观察到的类型 x 更改为 number , 我们仍然可以将 string 赋值给 x 。这是因为声明类型 x 开始是 string | number 。

如果我们分配了一个 boolean 给 x ,我们就会看到一个错误,因为它不是声明类型的一部分。

| | let x = Math.random() < 0.5 ? 10 : "hello world!"; |

| | // let x: string | number |

| | x = 1; |

| | |

| | // let x: number |

| | console.log(x); |

| | |

| | // 出错了~! |

| | x = true |

| | |

| | // let x: string | number |

| | console.log(x); |

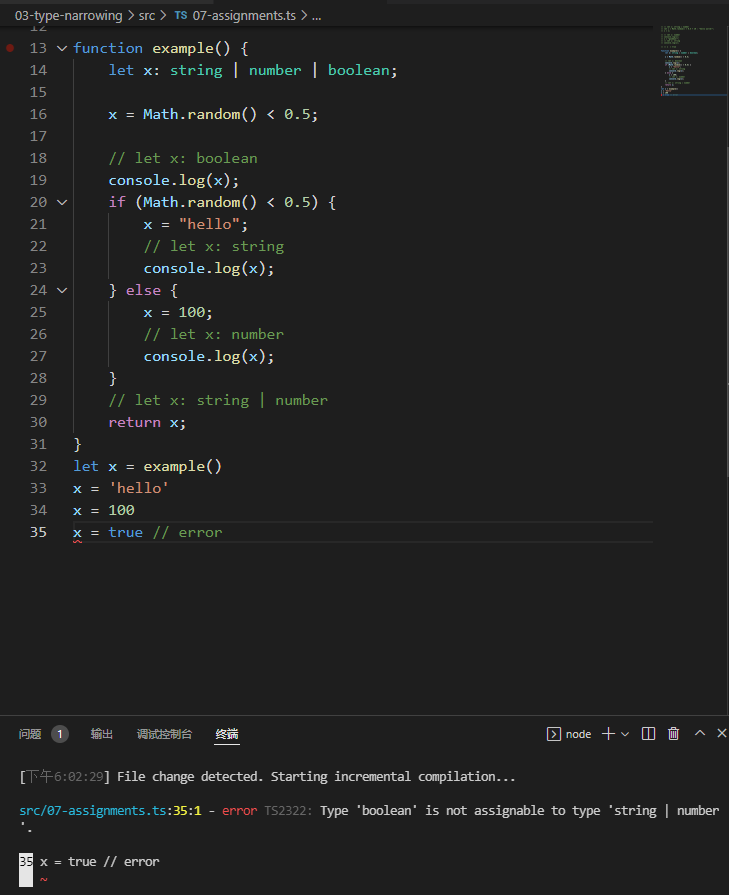

4.7 控制流分析

到目前为止, 我们已经通过一些基本实例来说明TS如何在特定分支中缩小范围. 但是除了从每个变量中走出来, 并在if、while 条件等中寻找类型保护之外, 还有更多的事情要做, 比如:

| | function padLeft(padding: number | string, input: string) { |

| | if (typeof padding === "number") { |

| | return new Array(padding + 1).join(" ") + input; |

| | } |

| | return padding + input; |

| | } |

padLeft从其第一个if块中返回. TS能够分析这段代码,并看到在padding是数字的情况下, 主体的其余部分( return padding + input; )是不可达的。因此,它能够将数字从 padding 的类型中移除(从string|number缩小到string),用于该函数的其余部分。

这种基于可达性的代码分析被称为控制流分析,TypeScript使用这种流分析来缩小类型,因为它遇到了 类型守卫和赋值。当一个变量被分析时,控制流可以一次又一次地分裂和重新合并,该变量可以被观察到在每个点上有不同的类型.

| | function example() { |

| | let x: string | number | boolean; |

| | |

| | x = Math.random() < 0.5; |

| | |

| | // let x: boolean |

| | console.log(x); |

| | if (Math.random() < 0.5) { |

| | x = "hello"; |

| | // let x: string |

| | console.log(x); |

| | } else { |

| | x = 100; |

| | // let x: number |

| | console.log(x); |

| | } |

| | // let x: string | number |

| | return x; |

| | } |

| | let x = example() |

| | x = 'hello' |

| | x = 100 |

| | x = true // error |

4.8 使用类型谓词

到目前为止,我们已经用现有的JavaScript结构来处理窄化问题,然而有时你想更直接地控制整个代码中的类型变化。

为了定义一个用户定义的类型保护,我们只需要定义一个函数,其返回类型是一个类型谓词.

| | type Fish = { |

| | name: string |

| | swim: () => void |

| | } |

| | |

| | type Bird = { |

| | name: string |

| | fly: () => void |

| | } |

| | function isFish(pet: Fish | Bird): pet is Fish { |

| | return (pet as Fish).swim !== undefined |

| | } |

在这个例子中, pet is Fish 是我们的类型谓词。谓词的形式是 parameterName is Type ,其中 parameterName 必须是当前函数签名中的参数名称, 返回一个boolean, 代表是不是该Type

任何时候 isFish 被调用时,如果原始类型是兼容的,TypeScript将把该变量缩小到该特定类型。

| | function getSmallPet(): Fish | Bird { |

| | let fish: Fish = { |

| | name: 'gold fish', |

| | swim: () => { |

| | console.log('fish is swimming.') |

| | } |

| | } |

| | let bird: Bird = { |

| | name: 'sparrow', |

| | fly: () => { |

| | console.log('bird is flying.') |

| | } |

| | } |

| | return Math.random() < 0.5 ? bird : fish |

| | } |

| | // 这里 pet 的 swim 和 fly 都可以访问了 |

| | let pet = getSmallPet() // |

| | console.log(pet) |

| | if (isFish(pet)) { |

| | pet.swim() |

| | } else { |

| | pet.fly() |

| | } |

注意,TypeScript不仅知道 pet 在 if 分支中是一条鱼;它还知道在 else 分支中,你没有一条 Fish ,所以你一定有一只 Bird 。

你可以使用类型守卫 isFish 来过滤 Fish | Bird 的数组,获得 Fish 的数组。

| | const zoo: (Fish | Bird)[] = [getSmallPet(), getSmallPet(), getSmallPet()] |

| | const underWater1: Fish[] = zoo.filter(isFish) |

| | console.log(underWater1) |

| | // 或者,等同于 |

| | const underWater2: Fish[] = zoo.filter(isFish) as Fish[] |

| | console.log(underWater2) |

| | |

| | // 对于更复杂的例子,该谓词可能需要重复使用 |

| | const underWatch3: Fish[] = zoo.filter((pet): pet is Fish => { |

| | if (pet.name === 'frog') { |

| | return false |

| | } |

| | return isFish(pet) |

| | }) |

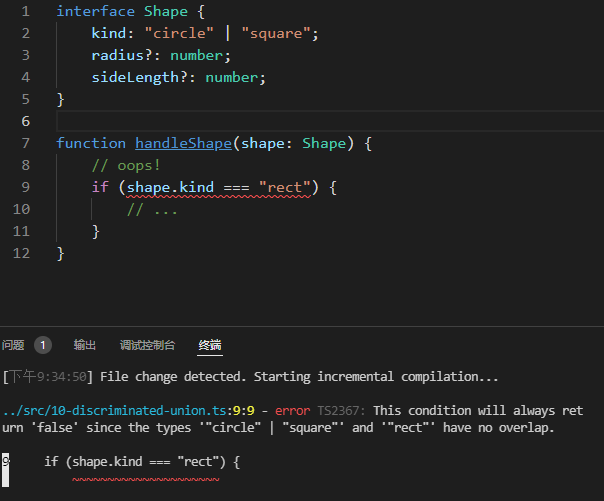

4.9 受歧视的unions

到目前为止,我们所看的大多数例子都是围绕着用简单的类型(如 string 、 boolean 和 number )来缩小单个变量。虽然这很常见,但在JavaScript中,大多数时候我们要处理的是稍微复杂的结构。

为了激发灵感,让我们想象一下,我们正试图对圆形和方形等形状进行编码。圆记录了它们的半径,方记录了它们的边长。我们将使用一个叫做 kind 的字段来告诉我们正在处理的是哪种形状。这里是定义 Shape 的第一个尝试。

| | interface Shape { |

| | kind: "circle" | "square"; |

| | radius?: number; |

| | sideLength?: number; |

| | } |

注意,我们使用的是字符串字面类型的联合。 "circle" 和 "square" 分别告诉我们应该把这个形状 当作一个圆形还是方形。通过使用 "circle" | "square " 而不是string ,我们可以避免拼写错误的问题。

| | function handleShape(shape: Shape) { |

| | // oops! |

| | if (shape.kind === "rect") { |

| | // ... |

| | } |

| | } |

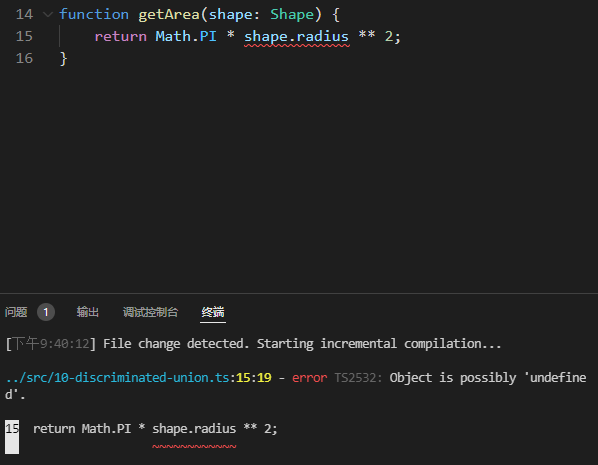

我们可以编写一个 getArea 函数,根据它处理的是圆形还是方形来应用正确的逻辑。我们首先尝试处理圆形。

| | function getArea(shape: Shape) { |

| | return Math.PI * shape.radius ** 2; |

| | } |

在strictNullChecks下,这给了我们一个错误——这是很恰当的,因为radius可能没有被定义。 但是如果我们对kind属性进行适当的检查呢?

| | function getArea(shape: Shape) { |

| | if (shape.kind === "circle") { |

| | return Math.PI * shape.radius ** 2; |

| | } |

| | } |

嗯, TypeScript 仍然不知道该怎么做。我们遇到了一个问题,即我们对我们的值比类型检查器知道的更多。我们可以尝试使用一个非空的断言 ( radius 后面的那个叹号 ! ) 来说明 radius 肯定存在。

| | function getArea(shape: Shape) { |

| | if (shape.kind === "circle") { |

| | return Math.PI * shape.radius! ** 2; |

| | } |

| | } |

但这感觉并不理想。我们不得不用那些非空的断言对类型检查器声明一个叹号(!),以说服它相信 shape.radius 是被定义的,但是如果我们开始移动代码,这些断言就容易出错。此外,在 strictNullChecks 之外,我们也可以意外地访问这些字段(因为在读取这些字段时,可选属性被认为总是存在的)。我们绝对可以做得更好.

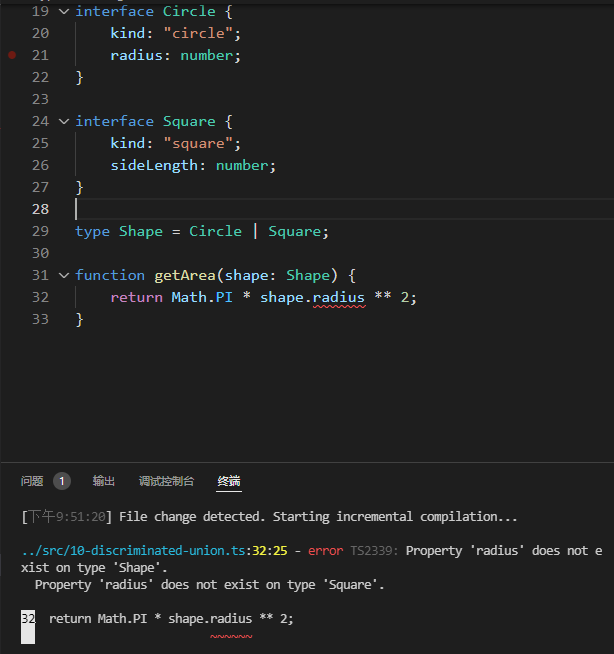

Shape 的这种编码的问题是,类型检查器没有办法根据种类属性知道 radius 或 sideLength 是否存在。我们需要把我们知道的东西传达给类型检查器。考虑到这一点,让我们再来定义一下Shape.

| | interface Circle { |

| | kind: "circle"; |

| | radius: number; |

| | } |

| | |

| | interface Square { |

| | kind: "square"; |

| | sideLength: number; |

| | } |

| | type Shape = Circle | Square; |

在这里,我们正确地将 Shape 分成了两种类型,为 kind 属性设置了不同的值,但是 radius 和 sideLength 在它们各自的类型中被声明为必需的属性。

让我们看看当我们试图访问 Shape 的半径时会发生什么。

| | function getArea(shape: Shape) { |

| | return Math.PI * shape.radius ** 2; |

| | } |

就像我们对 Shape 的第一个定义一样,这仍然是一个错误。当半径是可选的时候,我们得到了一个错误(仅在 strictNullChecks 中),因为 TypeScript 无法判断该属性是否存在。现在 Shape 是一个联合体,TypeScript 告诉我们 shape 可能是一个 Square ,而Square并没有定义半径 radius 。 这两种解释都是正确的,但只有我们对 Shape 的新编码仍然在 strictNullChecks 之外导致错误.

但是, 如果我们在此尝试检查kind属性呢?

| | function getArea(shape: Shape) { |

| | if (shape.kind === "circle") { |

| | // shape: Circle |

| | return Math.PI * shape.radius ** 2; |

| | } |

| | } |

这就摆脱了错误! 当 union 中的每个类型都包含一个与字面类型相同的属性时,TypeScript 认为这是一 个有区别的 union ,并且可以缩小 union 的成员。

在这种情况下, kind 就是那个共同属性(这就是 Shape 的判别属性)。检查 kind 属性是否为 "circle" ,就可以剔除 Shape 中所有没有 "circle" 类型属性的类型。这就把 Shape 的范围缩小到 了 Circle 这个类型。

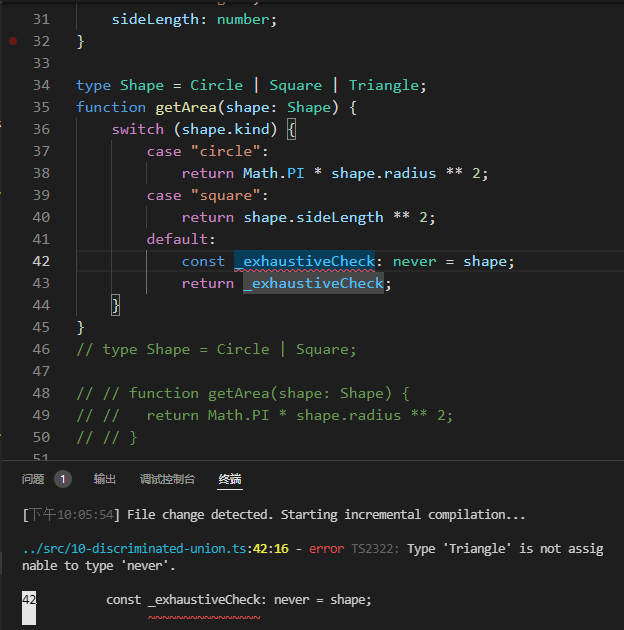

同样的检查方法也适用于 switch 语句。现在我们可以试着编写完整的 getArea ,而不需要任何讨厌 的叹号 ! 非空的断言。

| | function getArea(shape: Shape) { |

| | switch (shape.kind) { |

| | // shape: Circle |

| | case "circle": |

| | return Math.PI * shape.radius ** 2; |

| | // shape: Square |

| | case "square": |

| | return shape.sideLength ** 2; |

| | } |

| | } |

这里最重要的是 Shape 的编码。向 TypeScript 传达正确的信息是至关重要的,这个信息就是 Circle 和 Square 实际上是具有特定种类字段的两个独立类型。这样做让我们写出类型安全的TypeScript代码, 看起来与我们本来要写的JavaScript没有区别。从那里,类型系统能够做 "正确 "的事情,并找出我们 switch 语句的每个分支中的类型.

辨证的联合体不仅仅适用于谈论圆形和方形。它们适合于在JavaScript中表示任何类型的消息传递方案, 比如在网络上发送消息( client/server 通信),或者在状态管理框架中编码突变.

4.10 never类型与穷尽性检查

在缩小范围时,你可以将一个联合体的选项减少到你已经删除了所有的可能性并且什么都不剩的程度。 在这些情况下,TypeScript将使用一个 never 类型来代表一个不应该存在的状态。

never 类型可以分配给每个类型;但是,没有任何类型可以分配给never(除了never本身)。这意味着你可以使用缩小并依靠 never 的出现在 switch 语句中做详尽的检查。

例如,在我们的 getArea 函数中添加一个默认值,试图将形状分配给 never ,当每个可能的情况都没有被处理时,就会引发。

| | type Shape = Circle | Square; |

| | function getArea(shape: Shape) { |

| | switch (shape.kind) { |

| | case "circle": |

| | return Math.PI * shape.radius ** 2; |

| | case "square": |

| | return shape.sideLength ** 2; |

| | default: |

| | const \_exhaustiveCheck: never = shape; |

| | return \_exhaustiveCheck; |

| | } |

| | } |

在 Shape 联盟中添加一个新成员,将导致TypeScript错误

| | interface Triangle { |

| | kind: "triangle"; |

| | sideLength: number; |

| | } |

| | type Shape = Circle | Square | Triangle; |

| | function getArea(shape: Shape) { |

| | switch (shape.kind) { |

| | case "circle": |

| | return Math.PI * shape.radius ** 2; |

| | case "square": |

| | return shape.sideLength ** 2; |

| | default: |

| | const \_exhaustiveCheck: never = shape; |

| | return \_exhaustiveCheck; |

| | } |

| | } |

TypeScript学习第五章: 函数

函数是任何应用程序的基本构件,无论它们是本地函数,从另一个模块导入,还是一个类上的方法。它们也是值,就像其他值一样,TypeScript有很多方法来描述如何调用函数。让我们来学习一下如何编写描述函数的类型。

5.1 函数类型表达式

描述一个函数的最简单是用一个函数类型表达式. 这些类型在语法上类似于箭头函数.

| | function greeter(fn: (a: string) => void) { |

| | fn("Hello, World"); |

| | } |

| | function printToConsole(s: string) { |

| | console.log(s); |

| | } |

| | greeter(printToConsole); |

语法 (a: string) => void 意味着有一个参数的函数,名为 a ,类型为字符串,没有返回值"。就像函数声明一样,如果没有指定参数类型,它就隐含为 any 类型。

当然, 我们可以用一个类型别名来命名一个函数类型.

| | type GreetFunction = (a: string) => void; |

| | function greeter(fn: GreetFunction) { |

| | // ... |

| | } |

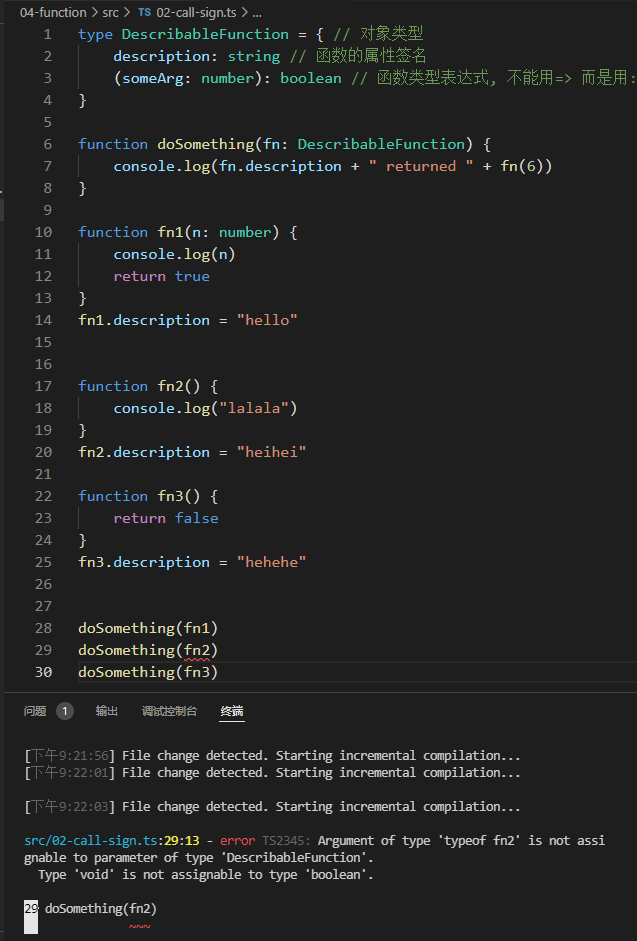

5.2 调用签名: 属性签名

在JavaScript中,除了可调用之外,函数还可以有属性。然而,函数类型表达式的语法不允许声明属性。 如果我们想用属性来描述可调用的东西,我们可以在一个类型别名中写一个调用签名。

值得注意的是, 类型别名中缩写的函数类型表达式返回值是用冒号:而不是箭头函数=>, 且实际应用时所传入函数返回值必须与此函数类型表达式声明的相同(fn1和fn2), 如果函数体内没有操作参数的行为, 可以不传参数(比如fn3).

| | type DescribableFunction = { // 对象类型 |

| | description: string // 函数的属性签名 |

| | (someArg: number): boolean // 函数类型表达式, 不能用=> 而是用: |

| | } |

| | |

| | function doSomething(fn: DescribableFunction) { |

| | console.log(fn.description + " returned " + fn(6)) |

| | } |

| | |

| | // 传入正常参数使用且正常返回值 |

| | function fn1(n: number) { |

| | console.log(n) |

| | return true |

| | } |

| | fn1.description = "hello" |

| | |

| | // 不传入参数且不正常返回值 |

| | function fn2() { |

| | console.log("lalala") |

| | } |

| | fn2.description = "heihei" |

| | |

| | // 不传入参数且正常返回值 |

| | function fn3() { |

| | return false |

| | } |

| | fn3.description = "hehehe" |

| | |

| | |

| | doSomething(fn1) // 正常 |

| | doSomething(fn2) // 报错 |

| | doSomething(fn3) // 正常 |

5.3 构造签名 new (params, ...): Ctor

JS函数也可以用new操作符来调用. TS将这些成为构造函数, 因为它们通常会创建一个新的对象。你可以通过在调用签名前面添加 new 关键字来写一个构造签名, 返回的是一个类或者构造函数.

| | class Ctor { |

| | s: string |

| | constructor(s: string) { |

| | this.s = s |

| | } |

| | } |

| | |

| | type SomeConstructor = { // 在调用签名前加new就是构造签名 |

| | new (s: string): Ctor // 返回的是一个构造函数或者类 |

| | } |

| | function fn(ctor: SomeConstructor) { // SomeConstructor可以理解为构造函数 |

| | return new ctor("hello") |

| | } |

| | |

| | const f = fn(Ctor) |

| | console.log(f.s) |

有些对象,如 JavaScript 的 Date 对象,可以在有 new 或没有 new 的情况下被调用。你可以在同一类型中任意地结合调用和构造签名.

| | interface CallOrConstruct { |

| | new (s: string): Date |

| | (): string |

| | } |

| | |

| | function fn(date: CallOrConstruct) { |

| | let d = new date('2021-11-20') |

| | let n = date() // 因为Date可以在不使用new的情况下调用所以代码正常 |

| | console.log(d) |

| | console.log(n) |

| | } |

| | |

| | fn(Date) |

下一个实例

| | // clock构造函数的接口, 是一个构造签名, 返回一个ClockInterface类的构造函数 |

| | interface ClockConstructor { |

| | new (hour: number, minute: number): ClockInterface; |

| | } |

| | |

| | // Clock类的接口, 里面有一个tick()函数 |

| | interface ClockInterface { |

| | tick(): void; |

| | } |

| | |

| | // 创建Clock类的函数 |

| | function createClock( |

| | ctor: ClockConstructor, |

| | hour: number, |

| | minute: number |

| | ): ClockInterface { |

| | return new ctor(hour, minute); |

| | } |

| | |

| | // 具体的类来实现ClockInterface, 必须要有tick函数 |

| | class DigitalClock implements ClockInterface { |

| | h: number |

| | m: number |

| | constructor(h: number, m: number) { |

| | this.h = h |

| | this.m = m |

| | } |

| | tick() { |

| | console.log("beep beep"); |

| | } |

| | } |

| | |

| | // 具体的类来实现ClockInterface, 必须要有tick函数 |

| | class AnalogClock implements ClockInterface { |

| | h: number |

| | m: number |

| | constructor(h: number, m: number) { |

| | this.h = h |

| | this.m = m |

| | } |

| | tick() { |

| | console.log("tick tock"); |

| | } |

| | } |

| | |

| | let digital = createClock(DigitalClock, 12, 17); |

| | let analog = createClock(AnalogClock, 7, 32); |

| | console.log(digital) |

| | analog.tick() |

5.4 泛型函数

在写一个函数时, 输入的类型与输出的类型有关, 或者两个输入的类型以某种方式相关, 这是常见的. 让我们考虑一下一个返回数组种第一个元素的函数.

| | function firstElement(arr: any[]) { |

| | return arr[0] |

| | } |

这个函数完成了它的工作,但不幸的是它的返回类型是 any 。如果该函数返回数组元素的类型会更好。

在TypeScript中,当我们想描述两个值之间的对应关系时,会使用泛型。我们通过在函数签名中声明一个类型参数来做到这一点:

| | function firstElement<Type>(arr: Type[]): Type | undefined { |

| | return arr[0] |

| | } |

通过给这个函数添加一个类型参数 Type ,并在两个地方使用它,我们已经在函数的输入(数组)和输出(返回值)之间建立了一个联系。现在当我们调用它时,一个更具体的类型就出来了:

| | // s 是 'string' 类型 |

| | const s = firstElement(["a", "b", "c"]); |

| | // n 是 'number' 类型 |

| | const n = firstElement([1, 2, 3]); |

| | // u 是 undefined 类型 |

| | const u = firstElement([]); |

5.4.1 类型推断

请注意, 在这个例子中, 我们没有必要指定类型. 类型是由TS推断出来的------自动选择.

我们也可以使用多个类型参数. 例如, 一个独立版本的map看起来可能是这样的:

| | function map<Input, Output>(arr: Input[], func: (arg: Input) => Output): Output[] { |

| | return arr.map(func) |

| | } |

| | |

| | // 参数'n'是'字符串'类型。 |

| | // 'parsed'是'number[]'类型。 |

| | const parsed = map(["1", "2", "3"], (n) => parseInt(n)); |

请注意,在这个例子中,TypeScript可以推断出输入类型参数的类型(从给定的字符串数组string),以及基于函数表达式的返回值(数字number)的输出类型参数。

5.4.2 限制条件

我们i经写了一些通用函数, 可以对任何类型的值进行操作. 有时我们想把两个值联系起来, 但只能对某个值的子集进行操作. 这种在这种情况下,我们可以使用一个约束条件来限制一个类型参数可以接受的类型。

让我们写一个函数,返回两个值中较长的值。要做到这一点,我们需要一个长度属性,是一个数字。我们通过写一个扩展子句将类型参数限制在这个类型上.

| | function longest<Type extends { length: number }>(a: Type, b: Type) { |

| | if (a.length >= b.length) { |

| | return a; |

| | } else { |

| | return b; |

| | } |

| | } |

| | // longerArray 的类型是 'number[]' |

| | const longerArray = longest([1, 2], [1, 2, 3]); |

| | // longerString 是 'alice'|'bob' 的类型。 |

| | const longerString = longest("alice", "bob"); |

| | // 错误! 数字没有'长度'属性 |

| | const notOK = longest(10, 100); |

在这个例子中,有一些有趣的事情需要注意。我们允许TypeScript推断 longest 的返回类型。返回类型推断也适用于通用函数。

因为我们将 Type 约束为 { length: number } ,所以我们被允许访问 a 和 b 参数的 .length 属 性。如果没有类型约束,我们就不能访问这些属性,因为这些值可能是一些没有长度属性的其他类型。

longerArray 和 longerString 的类型是根据参数推断出来的。记住,泛型就是把两个或多个具有相同类型的值联系起来。 最后,正如我们所希望的,对 longest(10, 100) 的调用被拒绝了,因为数字类型没有一个 .length 属性

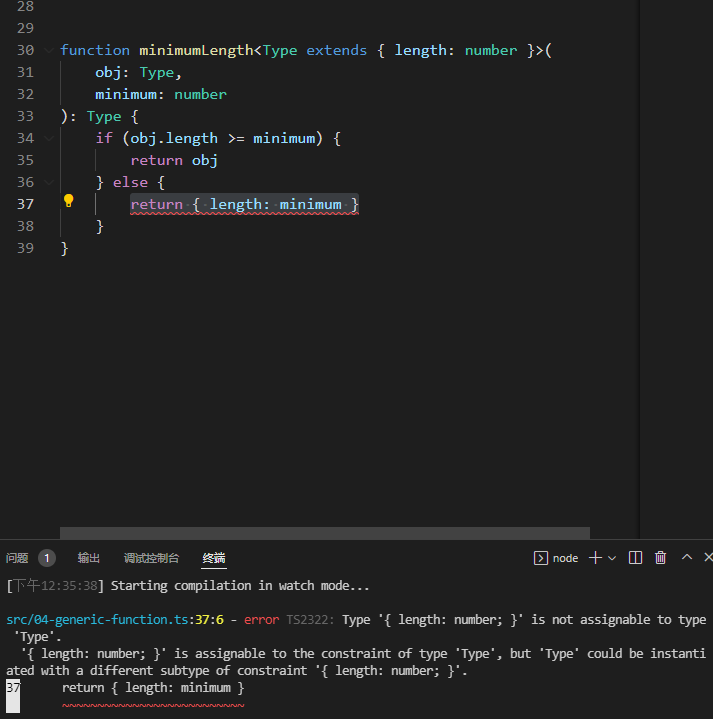

5.4.3 使用受限值

这里有一个使用通用约束条件时的常见错误。

| | function minimumLength<Type extends { length: number }>( |

| | obj: Type, |

| | minimum: number |

| | ): Type { |

| | if (obj.length >= minimum) { |

| | return obj |

| | } else { |

| | return { length: minimum } |

| | } |

| | } |

看起来这个函数没有问题--Type被限制为{ length: number },而且这个函数要么返回Type,要么返回一 个与该限制相匹配的值。问题是,该函数承诺返回与传入的对象相同的类型,而不仅仅是与约束条件相匹配的一些对象。如果这段代码是合法的,你可以写出肯定无法工作的代码。

| | // 'arr' 获得值: { length: 6 } |

| | const arr = minimumLength([1, 2, 3], 6); |

| | //在此崩溃,因为数组有一个'切片'方法,但没有返回对象! |

| | console.log(arr.slice(0)); |

5.4.4 指定类型参数

TypeScript 通常可以推断出通用调用中的预期类型参数,但并非总是如此。例如,假设你写了一个函数来合并两个数组:

| | function combine<Type>(arr1: Type[], arr2: Type[]): Type[] { |

| | return arr1.concat(arr2) |

| | } |

通常情况下,用不匹配的数组调用这个函数是一个错误:

| | const arr = combine([1, 2, 3], ["hello"]); |

然而,如果你打算这样做,你在调用函数时可以手动指定类型:

| | const arr = combine<string | number>([1, 2, 3], ["hello"]) |

5.4.5 编写优秀通用函数的准则

编写泛型函数很有趣,而且很容易被类型参数所迷惑。有太多的类型参数或在不需要的地方使用约束,会使推理不那么成功,使你的函数的调用者感到沮丧。

- 类型参数下推

下面是两种看似的函数写法:

| | function firstElement1<Type>(arr: Type[]) { |

| | return arr[0]; |

| | } |

| | function firstElement2<Type extends any[]>(arr: Type) { |

| | return arr[0]; |

| | } |

| | // a: number (推荐) |

| | const a = firstElement1([1, 2, 3]); |

| | // b: any (不推荐) |

| | const b = firstElement2([1, 2, 3]); |

乍一看,这些可能是相同的,但 firstElement1 是写这个函数的一个更好的方法。它的推断返回类型是Type,但 firstElement2 的推断返回类型是 any ,因为TypeScript必须使用约束类型来解析arr[0] 表达式,而不是在调用期间 "等待 "解析该元素。

规则: 在可能的情况下, 使用类型参数本身, 而不是对其进行约束

- 使用更少的类型参数

下面是另一对类似的函数:

| | function filter1<Type>(arr: Type[], func: (arg: Type) => boolean): Type[] { |

| | return arr.filter(func); |

| | } |

| | function filter2<Type, Func extends (arg: Type) => boolean>( |

| | arr: Type[], |

| | func: Func |

| | ): Type[] { |

| | return arr.filter(func); |

| | } |

我们已经创建了一个类型参数 Func ,它并不涉及两个值。这总是一个值得标记的坏习惯,因为它意味着想要指定类型参数的调用者必须无缘无故地手动指定一个额外的类型参数。 Func 除了使函数更难阅读和推理外,什么也没做。

规则: 总是尽可能少的使用类型参数

- 类型参数应该出现两次及以上

有时候我们会忘记, 一个函数可能不需要是通用的:

| | function greet<Str extends string>(s: Str) { |

| | console.log("Hello, " + s); |

| | } |

| | greet("world"); |

我们完全可以写一个更简单的版本:

| | function greet(s: string) { |

| | console.log("Hello, " + s); |

| | } |

记住,类型参数是用来关联多个值的类型的。如果一个类型参数在函数签名中只使用一次,那么它就没有任何关系。

规则: 如果一个类型的参数只出现在一个地方, 请重新考虑你是否真的需要它

5.5 可选参数 ?

JavaScript中的函数经常需要一个可变数量的参数。例如,number的 toFixed 方法需要一个可选的数字计数。

| | function f(n: number) { |

| | console.log(n.toFixed()); // 0 个参数 |

| | console.log(n.toFixed(3)); // 1 个参数 |

| | } |

我们可以在TypeScript中通过将参数用 ? 标记:

| | function f(x?: number) { |

| | // ... |

| | } |

| | f(); // 正确 |

| | f(10); // 正确 |

| | |

虽然参数被指定为 number 类型,但 x 参数实际上将具有 number | undefined 类型,因为在 JavaScript中未指定的参数会得到 undefined 的值。

你也可以提供一个参数默认值

| | function f(x = 10) { |

| | //... |

| | } |

现在在 f 的主体中, x 将具有 number 类型,因为任何 undefined 的参数将被替换为10 。请注意,当一个参数是可选的,调用者总是可以传递未定义的参数,因为这只是模拟一个 "丢失 "的参数:

| | declare function f(x?: number): void; |

| | |

| | // 以下调用都是正确的 |

| | f(); |

| | f(10); |

| | f(undefined); |

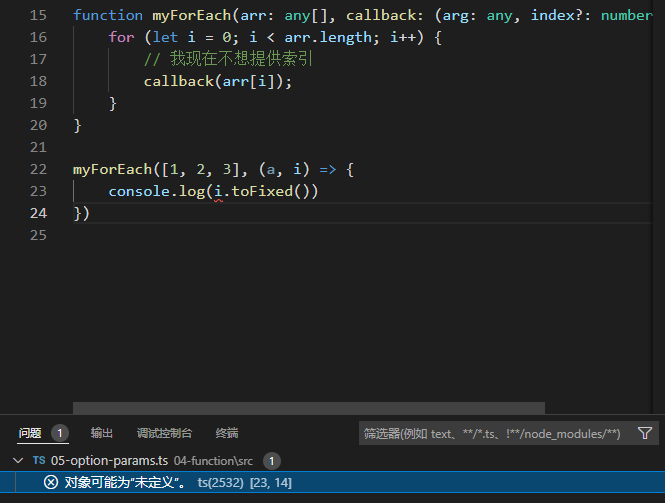

5.5.1 回调中的可选参数

一旦你了解了可选参数和函数类型表达式, 在编写调用回调的函数时就很容易犯以下错误:

| | function myForEach(arr: any[], callback: (arg: any, index?: number) => void) { |

| | for (let i = 0; i < arr.length; i++) { |

| | callback(arr[i], i); |

| | } |

| | } |

我们在写index?作为一个可选参数时, 通常是想让这些调用都是合法的:

| | myForEach([1, 2, 3], (a) => console.log(a)) |

| | myForEach([1, 2, 3], (a, i) => console.log(a, i)) |

这实际上意味着回调可能会被调用,只有一个参数。换句话说,该函数定义说,实现可能是这样的:

| | function myForEach(arr: any[], callback: (arg: any, index?: number) => void) { |

| | for (let i = 0; i < arr.length; i++) { |

| | // 我现在不想提供索引 |

| | callback(arr[i]); |

| | } |

| | } |

反过来,TypeScript会强制执行这个意思,并发出实际上不可能的错误:

| | myForEach([1, 2, 3], (a, i) => { |

| | console.log(i.toFixed()) |

| | }) |

在JavaScript中,如果你调用一个形参多于实参的函数,额外的参数会被简单地忽略。TypeScript的行为也是如此。

参数较少的函数(相同的类型)总是可以取代参数较多的函数的位置。

当为回调写一个函数类型时, 永远不要写一个可选参数, 除非你打算在不传递该参数的情况下调用函数.

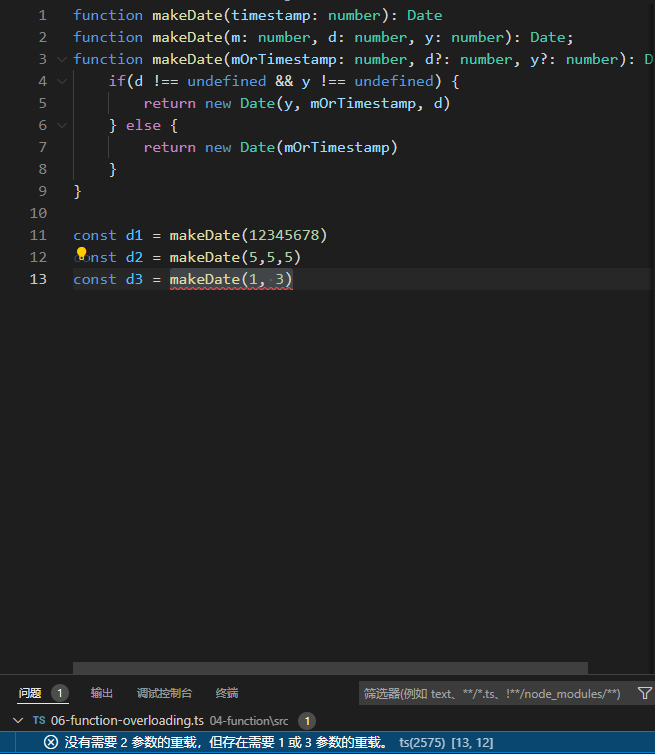

5.6 函数重载: 重载签名

一些 JavaScript 函数可以在不同的参数数量和类型中被调用。例如,你可能会写一个函数来产生一个 Date,它需要一个时间戳(一个参数)或一个月/日/年规格(三个参数)。

在TypeScript中,我们可以通过编写重载签名来指定一个可以以不同方式调用的函数。要做到这一点, 要写一些数量的函数签名(通常是两个或更多),然后是函数的主体:

| | function makeDate(timestamp: number): Date // 重载签名 |

| | function makeDate(m: number, d: number, y: number): Date // 重载签名 |

| | function makeDate(mOrTimestamp: number, d?: number, y?: number): Date { |

| | if(d !== undefined && y !== undefined) { |

| | return new Date(y, mOrTimestamp, d) |

| | } else { |

| | return new Date(mOrTimestamp) |

| | } |

| | } |

| | |

| | const d1 = makeDate(12345678) |

| | const d2 = makeDate(5,5,5) |

| | const d3 = makeDate(1, 3) |

在这个例子中,我们写了两个重载:一个接受一个参数,另一个接受三个参数。这前两个签名被称为重载签名。

然后,我们写了一个具有兼容签名的函数实现。函数有一个实现签名,但这个签名不能被直接调用。即使我们写了一个在所需参数之后有两个可选参数的函数,它也不能以两个参数被调用

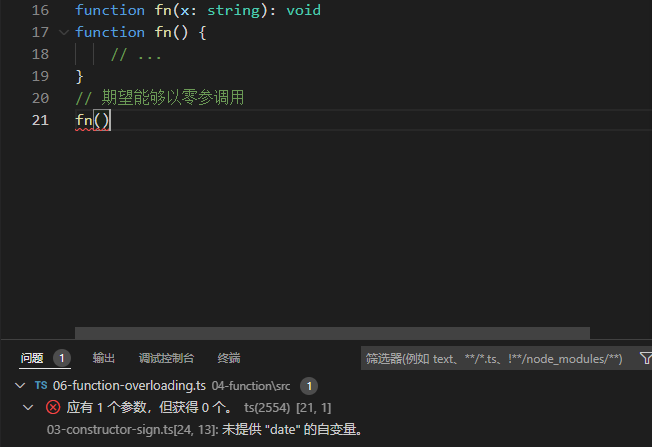

5.6.1 重载签名和实现签名

这是一个常简的混乱的来源. 通常我们会写这样的代码, 却不明白为什么会出现错误:

| | function fn(x: string): void |

| | function fn() { |

| | // ... |

| | } |

| | // 期望能够以零参调用 |

| | fn() |

同样, 用于编写函数体的签名不能从外面"看到":

实现的签名从外面是看不到的. 在编写重载函数时, 你应该总是在函数的实现上面有两个或多个签名.

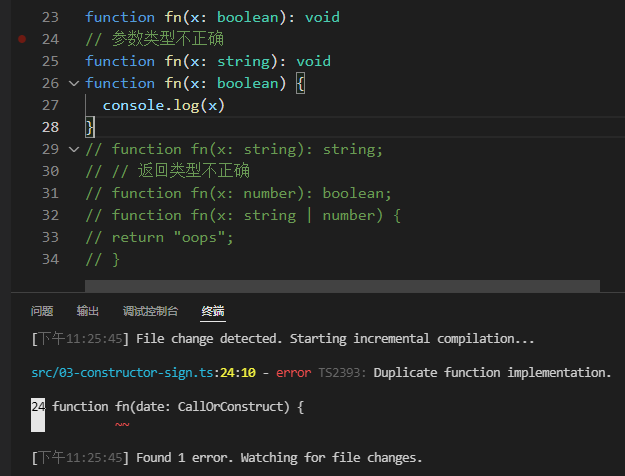

实现签名也必须与重载签名兼容. 例如, 这些函数有错误, 因为实现签名没有以正确的方式匹配重载:

| | function fn(x: boolean): void; |

| | // 参数类型不正确 |

| | function fn(x: string): void; |

| | function fn(x: boolean) {} |

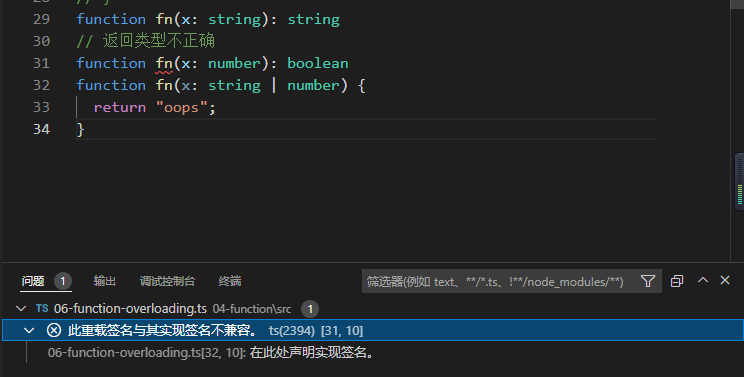

| | function fn(x: string): string |

| | // 返回类型不正确 |

| | function fn(x: number): boolean |

| | function fn(x: string | number) { |

| | return "oops"; |

| | } |

5.6.2 编写好的重载

和泛型一样,在使用函数重载时,有一些准则是你应该遵循的。遵循这些原则将使你的函数更容易调用,更容易理解,更容易实现。

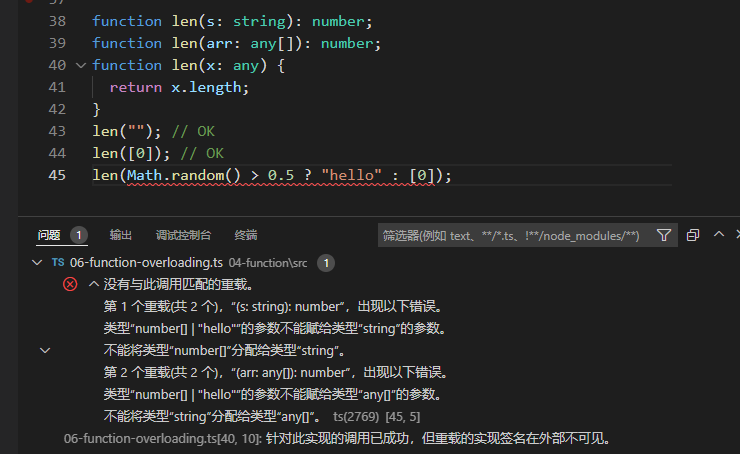

让我们考虑一个返回字符串或数组长度的函数:

| | function len(s: string): number; |

| | function len(arr: any[]): number; |

| | function len(x: any) { |

| | return x.length; |

| | } |

这个函数是好的;我们可以用字符串或数组来调用它。然而,我们不能用一个可能是字符串或数组的值来调用它,因为TypeScript只能将一个函数调用解析为一个重载:

| | len(""); // OK |

| | len([0]); // OK |

| | len(Math.random() > 0.5 ? "hello" : [0]); |

因为两个重载都有相同的参数数量和相同的返回类型,我们可以改写一个非重载版本的函数:

| | function len(x: any[] | string) { |

| | return x.length; |

| | } |

| | len(""); // OK |

| | len([0]); // OK |

| | len(Math.random() > 0.5 ? "hello" : [0]); // OK |

这就好得多了! 调用者可以用任何一种值来调用它,而且作为额外的奖励,我们不需要找出一个正确的实现签名。

在可能的情况下,总是倾向于使用联合类型的参数而不是重载参数

5.6.3 函数内This的声明

TS会通过代码分析来推断函数中this应该是什么, 比如下面的例子:

| | const user = { |

| | id: 123, |

| | admin: false, |

| | becomeAdmin: function () { |

| | this.admin = true; |

| | }, |

| | }; |

TS理解函数user.becomeAdmin有一个对应的this, 它是外部对象user. 这个对于很多情况来说已经足够了, 但是有很多情况下你需要更多的控制this代表什么对象/

JavaScript规范规定, 你不能有一个叫 this 的参数,所以TypeScript使用这个语法空间,让你在函数体中声明 this 的类型。

| | interface Card { |

| | suit: string; |

| | card: number; |

| | } |

| | interface Deck { |

| | suits: string[]; |

| | cards: number[]; |

| | createCardPicker(this: Deck): () => Card; |

| | } |

| | let deck: Deck = { |

| | suits: ["hearts", "spades", "clubs", "diamonds"], |

| | cards: Array(52), |

| | // NOTE: The function now explicitly specifies that its callee must be of type Deck |

| | createCardPicker: function(this: Deck) { |

| | return () => { |

| | let pickedCard = Math.floor(Math.random() * 52); |

| | let pickedSuit = Math.floor(pickedCard / 13); |

| | |

| | return {suit: this.suits[pickedSuit], card: pickedCard % 13}; |

| | } |

| | } |

| | } |

| | |

| | console.log(deck.createCardPicker()()) |

5.7 需要了解的其他类型

有一些额外的类型你会想要认识,它们在处理函数类型时经常出现。像所有的类型一样,你可以在任何地方使用它们,但这些类型在函数的上下文中特别相关.

5.7.1 void

void表示没有返回值的函数的返回值. 当一个函数没有任何返回语句, 或者没有从这些返回语句中返回任何明确的值时, 它都是推断出来void类型.

| | // 推断出的返回类型是void |

| | function noop() { |

| | return; |

| | } |

在JavaScript中,一个不返回任何值的函数将隐含地返回 undefinded 的值。然而,在TypeScript中, void 和 undefined 是不一样的。在本章末尾有进一步的细节。

void 和 undefined是不一样的

5.7.2 object

特殊类型object指的是任何不是基元的值( string 、 number 、 bigint 、 boolean 、 symbol 、 null 或 undefined )。这与空对象类型 { } 不同,也与全局类型 Object 不同。你很可能永远不会使用 Object 。

object不是Object。始终使用object!

请注意,在JavaScript中,函数值是对象。它们有属性,在它们的原型链中有 Object.prototype ,是 Object 的实例,你可以对它们调用 Object.key ,等等。由于这个原因,函数类型在TypeScript中被 认为是 object 。

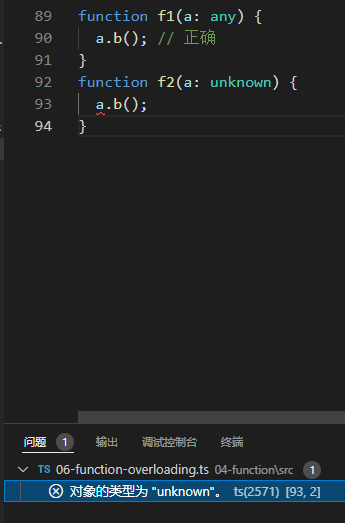

5.7.3 unknown

unknown类型代表任何值. 这与any类型相似, 但更安全, 因为对未知unknown值做任何事情都是不合法的.

| | function f1(a: any) { |

| | a.b(); // 正确 |

| | } |

| | function f2(a: unknown) { |

| | a.b(); |

| | } |

这在描述函数类型时很有用,因为你可以描述接受任何值的函数,而不需要在函数体中有 any 值。 反之,你可以描述一个返回未知类型的值的函数:

| | function safeParse(s: string): unknown { |

| | return JSON.parse(s); |

| | } |

| | |

| | // 需要小心对待'obj'! |

| | const obj = safeParse(someRandomString); |

5.7.4 never

有些函数永远不会返回一个值:

| | function fail(msg: string): never { |

| | throw new Error(msg); |

| | } |

never 类型标识永远不会被观察到的值. 载一个返回类型中, 这意味着函数抛出了一个异常或终止程序的执行.

never 也出现在TypeScript确定一个 union 中没有任何东西的时候。

| | function fn(x: string | number) { |

| | if (typeof x === "string") { |

| | // 做一些事 |

| | } else if (typeof x === "number") { |

| | // 再做一些事 |

| | } else { |

| | x; // 'never'! |

| | } |

5.7.5 Function

全局性的 Function 类型描述了诸如 bind 、 call 、 apply 和其他存在于JavaScript中所有函数值的属性。它还有一个特殊的属性,即 Function 类型的值总是可以被调用;这些调用返回 any 。

| | function doSomething(f: Function) { |

| | return f(1, 2, 3); |

| | } |

这是一个无类型的函数调用,一般来说最好避免,因为 any 返回类型都不安全。 如果你需要接受一个任意的函数,但不打算调用它,一般来说, () => void 的类型比较安全。

5.8 函数展开运算符

5.8.1 形参展开(Rest Parameters)

除了使用可选参数或重载来制作可以接受各种固定参数数量的函数之外,我们还可以使用休止参数来定义接受无限制数量的参数的函数。

rest 参数出现在所有其他参数之后,并使用 ... 的语法:

| | function multiply(n: number, ...m: number[]) { |

| | return m.map((x) => n * x); |

| | } |

| | // 'a' 获得的值 [10, 20, 30, 40] |

| | const a = multiply(10, 1, 2, 3, 4); |

在TypeScript中,这些参数的类型注解是隐含的 any[] ,而不是 any ,任何给出的类型注解必须是 Array 或 T[] 的形式,或一个元组类型(我们将在后面学习).

5.8.2 实参展开(Rest Arguments)

反之, 我们可以使用spread语法从数组中提供可变数量的参数. 例如数组的push方法需要任意数量的参数.

| | const arr1 = [1, 2, 3]; |

| | const arr2 = [4, 5, 6]; |

| | arr1.push(...arr2); |

| | console.log(arr1) //[ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 ] |

请注意,一般来说,TypeScript并不假定数组是不可变的。这可能会导致一些令人惊讶的行为。

| | // 推断的类型是 number[] -- "一个有零或多个数字的数组"。 |

| | // 不专指两个数字 |

| | const args = [8, 5]; |

| | const angle = Math.atan2(...args); |

这种情况的最佳解决方案取决于你的代码,但一般来说, const context 是最直接的解决方案

| | // 推断为2个长度的元组 |

| | const args = [8, 5] as const; |

| | // 正确 |

| | const angle = Math.atan2(...args); |

5.9 参数解构

可以使用参数重构来方便地将作为参数提供的对象,解压到函数主体的一个或多个局部变量中。在 JavaScript中,它看起来像这样:

| | function sum({ a, b, c }) { |

| | console.log(a + b + c); |

| | } |

| | sum({ a: 10, b: 3, c: 9 }); |

对象的类型注解在结构的语法之后:

| | function sum( { a, b, c }: { a: number, b: number, c: number }) { |

| | console.log(a + b + c) |

| | } |

这看起来有点啰嗦,但你也可以在这里使用一个命名的类型:

| | // 与之前的例子相同 |

| | type ABC = { a: number; b: number; c: number }; |

| | function sum({ a, b, c }: ABC) { |

| | console.log(a + b + c); |

| | } |

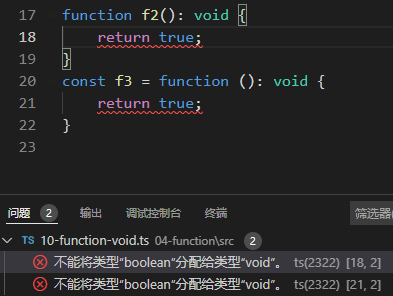

5.10 函数的可分配性: 返回void类型

函数的 void 返回类型可以产生一些不寻常的,但却是预期的行为。

返回类型为 void 的上下文类型并不强迫函数不返回东西。另一种说法是,一个具有 void 返回类型的上下文函数类型( type vf = () => void ),在实现时,可以返回任何其他的值,但它会被忽略。

因此,以下 () => void 类型的实现是有效的:

| | type voidFunc = () => void |

| | const f1: voidFunc = () => { |

| | return true |

| | } |

| | const f2: voidFunc = () => true |

| | const f3: voidFunc = function () { |

| | return true |

| | } |

而当这些函数之一的返回值被分配给另一个变量时,它将保留 void 的类型

| | const v1 = f1(); |

| | const v2 = f2(); |

| | const v3 = f3(); |

| | console.log(v1) // true |

| | console.log(v2) // true |

| | console.log(v3) // true |

这种行为的存在使得下面的代码是有效的,即使 Array.prototype.push 返回一个数字,而Array.prototype.forEach 方法期望一个返回类型为 void 的函数:

| | const src = [1, 2, 3]; |

| | const dst = [0]; |

| | src.forEach((el) => dst.push(el)); |

还有一个需要注意的特殊情况,当一个字面的函数定义有一个 void 的返回类型时,该函数必须不返回任何东西。

| | function f2(): void { |

| | return true; |

| | } |

| | const f3 = function (): void { |

| | return true; |

| | } |

TypeScript学习第六章: 对象类型

在JavaScript中,我们分组和传递数据的基本方式是通过对象。在TypeScript中,我们通过对象类型来表示这些对象。

正如我们所见,它们可以是匿名的:

| | function greet(person: { name: string; age: number }) { // 匿名对象{ name: string; age: number } |

| | return "Hello " + person.name; |

| | } |

或者可以通过使用一个接口来命名它们:

| | interface Person { // 接口中定义了一个对象类型,包含name和age |

| | name: string |

| | age: number |

| | } |

| | |

| | function greet(person: Person) { |

| | return 'Hello ' + person.name |

| | } |

或者类型别名

| | type Person = { // 类型别名种定义了一个对象类型, 其包含name和age |

| | name: string; |

| | age: number; |

| | }; |

| | function greet(person: Person) { |

| | return "Hello " + person.name; |

| | } |

在上面的三个例子中,我们写了一些函数,这些函数接收包含属性 name (必须是一个 string )和 age (必须是一个 number )的对象.

6.1 属性修改器

对象类型中的每个属性都可以指定几件事:类型、属性是否是可选的,以及属性是否可以被写入。

6.2 可选属性

很多时候,我们会发现自己处理的对象可能有一个属性设置。在这些情况下,我们可以在这些属性的名 字后面加上一个问号(?),把它们标记为可选的

| | type Shape = {} |

| | |

| | interface PaintOptions { |

| | shape: Shape; |

| | xPos?: number; |

| | yPos?: number; |

| | } |

| | |

| | function paintShape(opts: PaintOptions) { |

| | // ... |

| | } |

| | |

| | const shape: Shape = {} |

| | paintShape({ shape }); |

| | paintShape({ shape, xPos: 100 }); |

| | paintShape({ shape, yPos: 100 }); |

| | paintShape({ shape, xPos: 100, yPos: 100 }); |

在这个例子中, xPos 和 yPos 都被认为是可选的。我们可以选择提供它们中的任何一个,所以上面对 paintShape 的每个调用都是有效的。所有的可选性实际上是说,如果属性被设置,它最好有一个特定 的类型。

我们也可以从这些属性中读取,但当我们在 strictNullChecks 下读取时,TypeScript会告诉我们它们可能是未定义的。因为未赋值时值为undefined.

| | function paintShape(opts: PaintOptions) { |

| | let xPos = opts.xPos; |

| | let yPos = opts.yPos; |

| | // ... |

| | } |

在JavaScript中,即使该属性从未被设置过,我们仍然可以访问它--它只是会给我们未定义的值。我们可以专门处理未定义。

| | function paintShape(opts: PaintOptions) { |

| | let xPos = opts.xPos === undefined ? 0 : opts.xPos; |

| | let yPos = opts.yPos === undefined ? 0 : opts.yPos; |

| | // ... |

| | } |

请注意,这种为未指定的值设置默认值的模式非常普遍,以至于JavaScript有语法来支持它。

| | function paintShape({ shape, xPos = 0, yPos = 0 }: PaintOptions) {// 注意, 此时用了解构的语法, 将PaintOptions里的参数结构出来, 并给xPos和yPos设置了默认值 |

| | console.log("x coordinate at", xPos); |

| | console.log("y coordinate at", yPos); |

| | // ... |

| | } |

在这里,我们为 paintShape 的参数使用了一个解构模式,并为 xPos 和 yPos 提供了默认值。现在 xPos 和 yPos 都肯定存在于 paintShape 的主体中,但对于 paintShape 的任何调用者来说是可选 的。

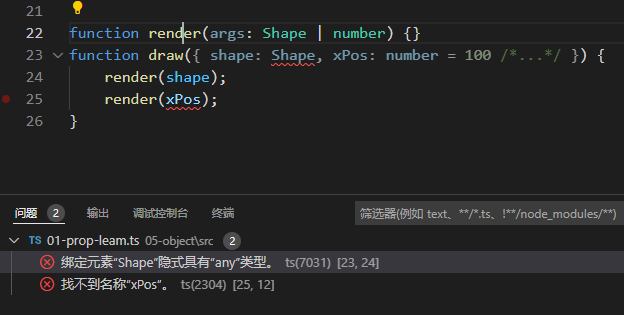

请注意,目前还没有办法将类型注释放在解构模式中。这是因为下面的语法在JavaScript中已经有了不同的含义。

| | function redner(args: Shape | number) {} |

| | function draw({ shape: Shape, xPos: number = 100 /*...*/ }) { |

| | render(shape); |

| | render(xPos); |

| | } |

在一个对象解构模式中, shape: Shape 意味着 "获取属性 shape ,并在本地重新定义为一个名为 Shape 的变量。同样, xPos: number 创建一个名为number的变量,其值基于参数的 xPos 。

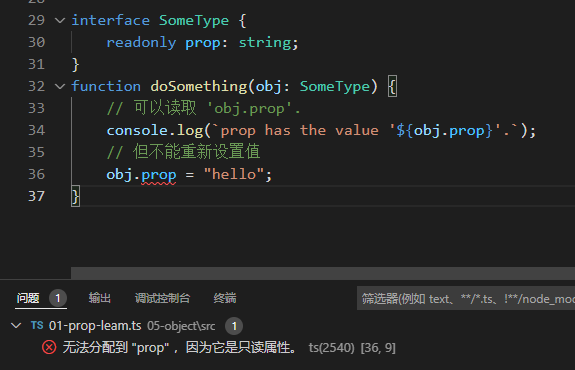

6.3 只读属性

对于TypeScript,属性也可以被标记为只读。虽然它不会在运行时改变任何行为,但在类型检查期间, 可以在一个属性前加readonly一个标记为只读的属性不能被写入.

| | interface SomeType { |

| | readonly prop: string; |

| | } |

| | function doSomething(obj: SomeType) { |

| | // 可以读取 'obj.prop'. |

| | console.log(`prop has the value '${obj.prop}'.`); |

| | // 但不能重新设置值 |

| | obj.prop = "hello"; |

| | } |

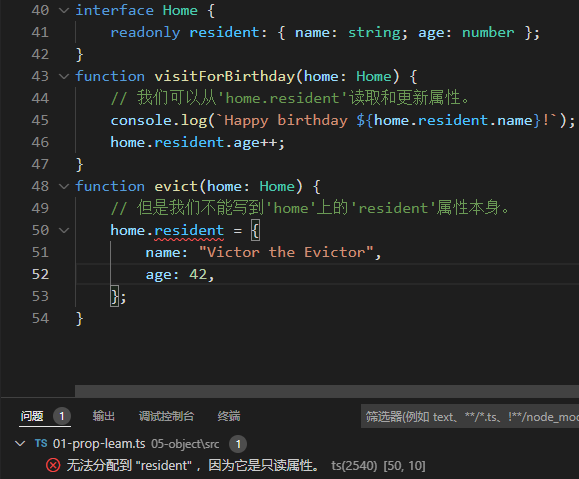

使用 readonly 修饰符并不一定意味着一个值是完全不可改变的。或者换句话说,它的内部内容不能被 改变,它只是意味着该属性本身不能被重新写入。

| | interface Home { |

| | readonly resident: { name: string; age: number }; |

| | } |

| | function visitForBirthday(home: Home) { |

| | // 我们可以从'home.resident'读取和更新属性。 |

| | console.log(`Happy birthday ${home.resident.name}!`); |

| | home.resident.age++; |

| | } |

| | function evict(home: Home) { |

| | // 但是我们不能写到'home'上的'resident'属性本身。 |

| | home.resident = { |

| | name: "Victor the Evictor", |

| | age: 42, |

| | }; |

| | } |

管理对 readonly 含义的预期是很重要的。在TypeScript的开发过程中,对于一个对象应该如何被使用 的问题,它是有用的信号。TypeScript在检查两个类型的属性是否兼容时,并不考虑这些类型的属性是 否是 readonly ,所以 readony 属性也可以通过别名来改变.

| | interface Person { |

| | name: string; |

| | age: number; |

| | } |

| | interface ReadonlyPerson { |

| | readonly name: string; |

| | readonly age: number; |

| | } |

| | let writablePerson: Person = { |

| | name: "Person McPersonface", |

| | age: 42, |

| | }; |

| | // 正常工作 |

| | let readonlyPerson: ReadonlyPerson = writablePerson; |

| | console.log(readonlyPerson.age); // 打印 '42' |

| | writablePerson.age++; |

| | console.log(readonlyPerson.age); // 打印 '43' |

6.4 索引签名

有时你并不提前知道一个类型的所有属性名称,但你知道值的类型。

在这些情况下,你可以使用一个索引签名来描述可能的值的类型,比如说:

| | interface StringArray { |

| | [index: number]: string; |

| | } |

| | const myArray: StringArray = ['a', 'b']; |

| | const secondItem = myArray[1]; |

上面,我们有一个 StringArray 接口,它有一个索引签名。这个索引签名指出,当一个 StringArray 被数字索引时,它将返回一个字符串。

索引签名的属性类型必须是 string 或 number 。

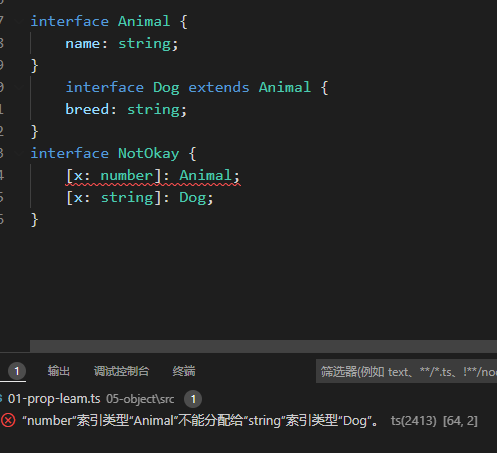

支持两种类型的索引器是可能的,但是从数字索引器返回的类型必须是字符串索引器返回的类型的子类型。这是因为当用 "数字 "进行索引时,JavaScript实际上在索引到一个对象之前将其转换为 "字符串"。这意味着用 100 (一个数字)进行索引和用 "100" (一个字符串)进行索引是一样的,所以两者需要一致。

| | interface Animal { |

| | name: string; |

| | } |

| | interface Dog extends Animal { |

| | breed: string; |

| | } |

| | interface NotOkay { |

| | [x: number]: Animal; |

| | [x: string]: Dog; |

| | } |

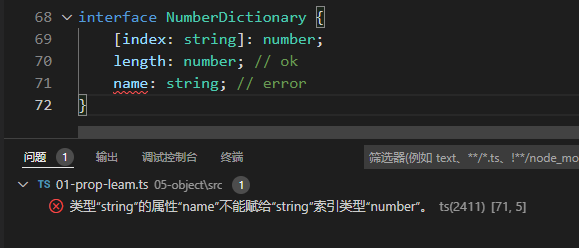

虽然字符串索引签名是描述 "字典 "模式的一种强大方式,但它也强制要求所有的属性与它们的返回类型相匹配。这是因为字符串索引声明 obj.property 也可以作为 obj["property"] 。在下面的例子中, name 的类型与字符串索引的类型不匹配,类型检查器会给出一个错误:

| | interface NumberDictionary { |

| | [index: string]: number; |

| | length: number; // ok |

| | name: string; // error |

| | } |

然而,如果索引签名是属性类型的联合,不同类型的属性是可以接受的:

| | interface NumberOrStringDictionary { |

| | [index: string]: number | string; |

| | length: number; // 正确, length 是 number 类型 |

| | name: string; // 正确, name 是 string 类型 |

| | } |

最后,你可以使索引签名为只读,以防止对其索引的赋值:

| | interface ReadonlyStringArray { |

| | readonly [index: number]: string; |

| | } |

| | let myArray: ReadonlyStringArray = getReadOnlyStringArray(); |

| | myArray[2] = "Mallory"; |

你不能设置 myArray[2] ,因为这个索引签名是只读的。

6.5 扩展类型

有一些类型可能是其他类型的更具体的版本,这是很常见的。例如,我们可能有一个 BasicAddress 类 型,描述发送信件和包裹所需的字段。

| | interface BasicAddress { |

| | name?: string; |

| | street: string; |

| | city: string; |

| | country: string; |

| | postalCode: string; |

| | } |

在某些情况下,这就足够了,但是如果一个地址的小区内有多个单元,那么地址往往有一个单元号与之 相关。我们就可以描述一个 AddressWithUnit :

| | interface AddressWithUnit { |

| | name?: string; |

| | unit: string; |

| | street: string; |

| | city: string; |

| | country: string; |

| | postalCode: string; |

| | } |

这就完成了工作,但这里的缺点是,当我们的变化是纯粹的加法时,我们不得不重复 BasicAddress 的 所有其他字段。相反,我们可以扩展原始的 BasicAddress 类型,只需添加 AddressWithUnit 特有的 新字段:

| | interface BasicAddress { |

| | name?: string; |

| | street: string; |

| | city: string; |

| | country: string; |

| | postalCode: string; |

| | } |

| | |

| | interface AddressWithUnit extends BasicAddress { |

| | unit: string; |

| | } |

接口上的 extends 关键字,允许我们有效地从其他命名的类型中复制成员,并添加我们想要的任何新成员。这对于减少我们不得不写的类型声明模板,以及表明同一属性的几个不同声明可能是相关的意图来说,是非常有用的。例如, AddressWithUnit 不需要重复 street 属性,而且因为 street 源于 BasicAddress ,我们会知道这两种类型在某种程度上是相关的。

接口也可以从多个类型中扩展。

| | interface Colorful { |

| | color: string; |

| | } |

| | interface Circle { |

| | radius: number; |

| | } |

| | interface ColorfulCircle extends Colorful, Circle {} |

| | |

| | const cc: ColorfulCircle = { |

| | color: "red", |

| | radius: 42, |

| | } |

6.6 交叉类型

接口允许我们通过扩展其他类型建立起新的类型。TypeScript提供了另一种结构,称为交叉类型,主要用于组合现有的对象类型。

叉类型是用 & 操作符定义的.

| | interface Colorful { |

| | color: string; |

| | } |

| | interface Circle { |

| | radius: number; |

| | } |

| | type ColorfulCircle = Colorful & Circle; |

| | |

| | const cc: ColorfulCircle = { |

| | color: "red", |

| | radius: 42, |

| | } |

在这里,我们将 Colorful 和 Circle 相交,产生了一个新的类型,它拥有 Colorful 和 Circle 的 所有成员。

| | function draw(circle: Colorful & Circle) { |

| | console.log(`Color was ${circle.color}`); |

| | console.log(`Radius was ${circle.radius}`); |

| | } |

| | // 正确 |

| | draw({ color: "blue", radius: 42 }); |

| | // 错误 |

| | draw({ color: "red", raidus: 42 }); |

6.7 接口与交叉类型

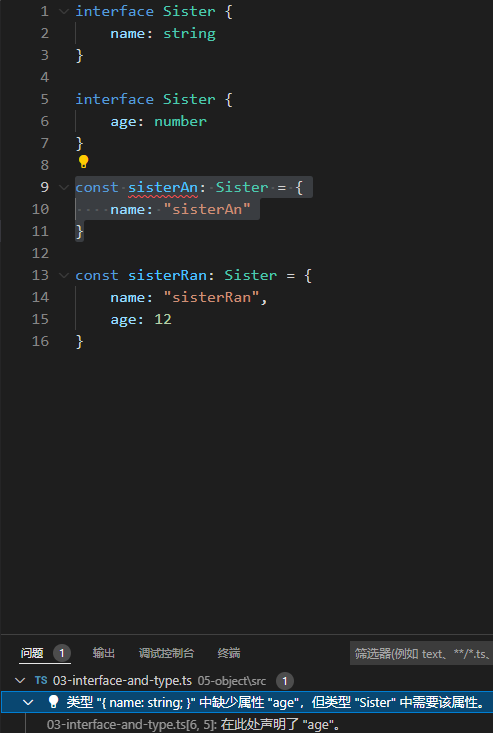

我们刚刚看了两种组合类型的方法,它们很相似,但实际上有细微的不同。对于接口,我们可以使用 extends 子句来扩展其他类型,而对于交叉类型,我们也可以做类似的事情,并用类型别名来命名结 果。两者之间的主要区别在于如何处理冲突,这种区别通常是你在接口和交叉类型的类型别名之间选择 一个的主要原因之一。

接口可以定义多次, 多次的声明会自动合并

| | interface Sister { |

| | name: string |

| | } |

| | |

| | interface Sister { |

| | age: number |

| | } |

| | const sisterAn: Sister = { |

| | name: "sisterAn" |

| | } |

| | const sisterRan: Sister = { |

| | name: "sisterRan", |

| | age: 12 |

| | } |

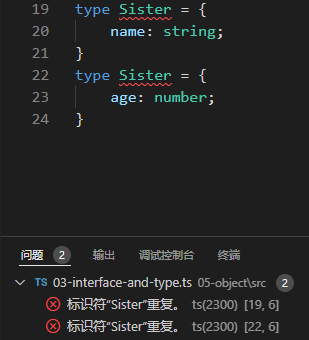

但是类型别名如果定义多次,会报错:

| | type Sister = { |

| | name: string; |

| | } |

| | type Sister = { |

| | age: number; |

| | } |

6.8 泛型对象类型

让我们想象一下,一个可以包含任何数值的盒子类型:字符串、数字、长颈鹿,等等.

| | interface Box { |

| | contents: any; |

| | } |

现在,内容属性的类型是任意,这很有效,但会导致下一步的意外。

我们可以使用 unknown ,但这意味着在我们已经知道内容类型的情况下,我们需要做预防性检查,或者使用容易出错的类型断言。

| | interface Box { |

| | contents: unknown; |

| | } |

| | |

| | let x: Box = { |

| | contents: "hello world", |

| | }; |

| | |

| | // 我们需要检查 'x.contents' |

| | if (typeof x.contents === "string") { |

| | console.log(x.contents.toLowerCase()); |

| | } |

| | |

| | // 或者用类型断言 |

| | console.log((x.contents as string).toLowerCase()); |

一种安全的方法是为每一种类型的内容搭建不同的盒子类型:

| | interface NumberBox { |

| | contents: number; |

| | } |

| | |

| | interface StringBox { |

| | contents: string; |

| | } |

| | |

| | interface BooleanBox { |

| | contents: boolean; |

| | } |

但这意味着我们必须创建不同的函数,或函数的重载,以对这些类型进行操作:

| | function setContents(box: StringBox, newContents: string): void; |

| | function setContents(box: NumberBox, newContents: number): void; |

| | function setContents(box: BooleanBox, newContents: boolean): void; |

| | function setContents(box: { contents: any }, newContents: any) { |

| | box.contents = newContents; |

| | } |

那是一个很大的模板。此外,我们以后可能需要引入新的类型和重载。这是令人沮丧的,因为我们的盒 子类型和重载实际上都是一样的.

相反, 我们可以做一个通用的Box类型, 声明一个参数类型:

| | interface Box<Type> { |

| | contents: Type |

| | } |

你可以把这句话理解为:"一个类型的盒子,是它的内容具有类型的东西"。以后,当我们引用 Box 时, 我们必须给一个类型参数来代替 Type 。

| | let box: Box<string> |

把 Box 想象成一个真实类型的模板,其中 Type 是一个占位符,会被替换成其他类型。当 TypeScript看到 Box 时,它将用字符串替换 Box 中的每个 Type 实例,并最终以 { contents: string } 这样的方式工作。换句话说, Box 和我们之前的 StringBox 工作起来是一样的。

| | interface Box<Type> { |

| | contents: Type; |

| | } |

| | interface StringBox { |

| | contents: string; |

| | } |

| | let boxA: Box<string> = { contents: "hello" }; |

| | boxA.contents; |

| | |

| | let boxB: StringBox = { contents: "world" }; |

| | boxB.contents; |

| | |

盒子是可重用的,因为Type可以用任何东西来代替。这意味着当我们需要一个新类型的盒子时,我们根 本不需要声明一个新的盒子类型(尽管如果我们想的话,我们当然可以)。

| | interface Box<Type> { |

| | contents: Type; |

| | } |

| | |

| | interface Apple { |

| | // .... |

| | } |

| | |

| | // 等价于 '{ contents: Apple }'. |

| | type AppleBox = Box<Apple>; |

这也意味着我们可以完全避免重载,而是使用通用函数。

| | function setContents<Type>(box: Box<Type>, newContents: Type) { |

| | box.contents = newContents; |

| | } |

通过使用一个类型别名来代替:

| | type Box<Type> = { |

| | contents: Type; |

| | } |

由于类型别名与接口不同,它不仅可以描述对象类型,我们还可以用它来编写其他类型的通用辅助类 型。

| | type OrNull<Type> = Type | null; |

| | type OneOrMany<Type> = Type | Type[]; |

| | type OneOrManyOrNull<Type> = OrNull<OneOrMany<Type>>; |

| | type OneOrManyOrNullStrings = OneOrManyOrNull<string>; |

我们将在稍后回到类型别名。

通用对象类型通常是某种容器类型,它的工作与它们所包含的元素类型无关。数据结构以这种方式工作是很理想的,这样它们就可以在不同的数据类型中重复使用。

6.9 数组类型

我们一直在使用这样一种类型:数组类型。每当我们写出 number[] 或 string[] 这样的类型时,这 实际上只是 Array 和 Array 的缩写:

| | function doSomething(value: Array<string>) { |

| | // ... |

| | } |

| | |

| | let myArray: string[] = ["hello", "world"]; |

| | |

| | // 这两样都能用 |

| | doSomething(myArray); |

| | doSomething(new Array("hello", "world")); |

和上面的 Box 类型一样, Array 本身也是一个通用类型。

| | interface Array<Type> { |

| | /** |

| | * 获取或设置数组的长度。 |

| | */ |

| | length: number; |

| | |

| | /** |

| | * 移除数组中的最后一个元素并返回。 |

| | */ |

| | pop(): Type | undefined; |

| | |

| | /** |

| | * 向一个数组添加新元素,并返回数组的新长度。 |

| | */ |

| | push(...items: Type[]): number; |

| | // ... |

| | } |

现代JavaScript还提供了其他通用的数据结构,比如 Map , Set , 和 Promise 。这实际上意味着,由于 Map 、 Set 和 Promise 的行为方式,它们可以与任何类型的集合一起工作。

6.10 只读数组类型

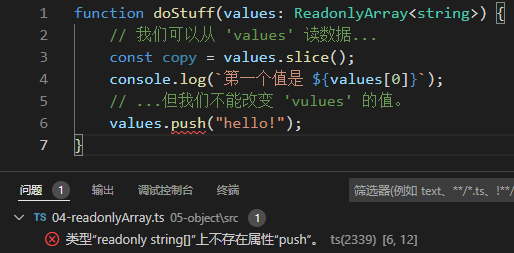

ReadonlyArray 是一个特殊的类型,描述了不应该被改变的数组。

| | function doStuff(values: ReadonlyArray<string>) { |

| | // 我们可以从 'values' 读数据... |

| | const copy = values.slice(); |

| | console.log(`第一个值是 ${values[0]}`); |

| | // ...但我们不能改变 'vulues' 的值。 |

| | values.push("hello!"); |

| | } |

和属性的 readonly 修饰符一样,它主要是一个我们可以用来了解意图的工具。当我们看到一个返回ReadonlyArrays 的函数时,它告诉我们我们根本不打算改变其内容,而当我们看到一个消耗ReadonlyArrays 的函数时,它告诉我们可以将任何数组传入该函数,而不用担心它会改变其内容。

与 Array 不同,没有一个我们可以使用的 ReadonlyArray 构造函数。

| | new ReadonlyArray("red", "green", "blue"); |

相反,我们可以将普通的 Array 分配给 ReadonlyArray 。

| | const roArray: ReadonlyArray<string> = ["red", "green", "blue"]; |

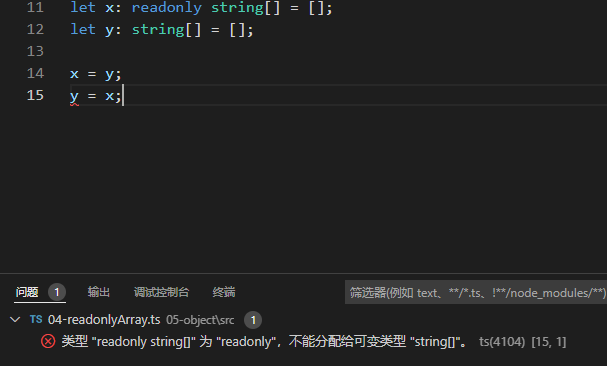

正如 TypeScript为 Array 提供了 Type[] 的速记语法一样,它也为 ReadonlyArray提 供了只读 Type[] 的速记语法。

最后要注意的是,与 readony 属性修改器不同,可分配性在普通 Array 和 ReadonlyArray 之间不是 双向的。

| | let x: readonly string[] = []; |

| | let y: string[] = []; |

| | |

| | x = y; |

| | y = x; |

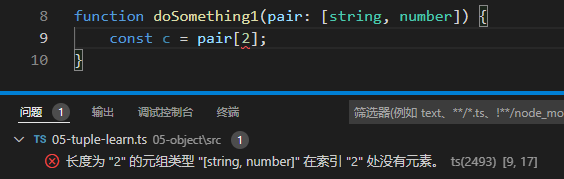

6.11 元组类型

Tuple 类型是另一种 Array 类型,它确切地知道包含多少个元素,以及它在特定位置包含哪些类型。

| | type StringNumberPair = [string, number]; |

这里, StringNumberPair 是一个 string 和 number 的元组类型。像 ReadonlyArray 一样,它在运行时没有表示,但对TypeScript来说是重要的。对于类型系统来说, StringNumberPair 描述了其 索引 0 包含字符串和 索引1 包含数字的数组。

| | function doSomething(pair: [string, number]) { |

| | const a = pair[0]; |

| | const b = pair[1]; |

| | // ... |

| | } |

| | doSomething(["hello", 42]) |

如果我们试图索引超过元素的数量,我们会得到一个错误:

| | function doSomething(pair: [string, number]) { |

| | const c = pair[2]; |

| | } |

我们还可以使用JavaScript的数组析构来对元组进行解构。

| | function doSomething(stringHash: [string, number]) { |

| | const [inputString, hash] = stringHash; |

| | console.log(inputString); |

| | console.log(hash); |

| | } |

除了这些长度检查,像这样的简单元组类型等同于 Array 的版本,它为特定的索引声明属性,并且用数字字面类型声明长度。

| | interface StringNumberPair { |

| | // 专有属性 |

| | length: 2; |

| | 0: string; |

| | 1: number; |

| | // 其他 'Array' 成员... |

| | slice(start?: number, end?: number): Array<string | number>; |

| | } |

另一件你可能感兴趣的事情是,元组可以通过在元素的类型后面写出问号(?)—— 可选的元组,元素 只能出现在末尾,而且还影响到长度的类型。

| | type Either2dOr3d = [number, number, number?]; |

| | function setCoordinate(coord: Either2dOr3d) { |

| | const [x, y, z] = coord; |

| | console.log(`提供的坐标有 ${coord.length} 个维度`); |

| | } |

图元也可以有其余元素,这些元素必须是 array/tuple 类型.

| | type StringNumberBooleans = [string, number, ...boolean[]]; |

| | type StringBooleansNumber = [string, ...boolean[], number]; |

| | type BooleansStringNumber = [...boolean[], string, number]; |

StringNumberBooleans描述了一个元组,其前两个元素分别是字符串和数字,但后面可以有任意数量的布尔。StringBooleansNumber描述了一个元组,其第一个元素是字符串,然后是任意数量的布尔运算,最后是一个数字。BooleansStringNumber描述了一个元组,其起始元素是任意数量的布尔运算,最后是一个字符 串,然后是一个数字。

一个有其余元素的元组没有集合的 "长度"——它只有一组不同位置的知名元素。

| | function readButtonInput(...args: [string, number, ...boolean[]]) { |

| | const [name, version, ...input] = args; |

| | console.log(name) |

| | console.log(version) |

| | console.log(input) |

| | |

| | // ... |

| | } |

| | |

| | const data: boolean[] = [true, false, true] |

| | const args:[string, number, ...boolean[]] = ["Hello world", 100, ...data] |

| | console.log(args) |

| | readButtonInput(...args) |

| | // [ 'Hello world', 100, true, false, true ] |

| | // Hello world |

| | // 100 |

| | // [ true, false, true ] |

基本上等同于:

| | function readButtonInput(name: string, version: number, ...input: boolean[]) { |

| | // ... |

| | } |

当你想用一个其余(rest)参数接受可变数量的参数,并且你需要一个最小的元素数量,但你不想引入中间变量时,这很方便。

6.12 只读元组类型

关于 tuple 类型的最后一点说明: tuple 类型有只读特性,可以通过在它们前面粘贴一个 readonly 修饰符来指定——就像数组的速记语法一样.

| | function doSomething(pair: readonly [string, number]) { |

| | // ... |

| | } |

正如你所期望的,在TypeScript中不允许向只读元组的任何属性写入:

| | function doSomething(pair: readonly [string, number]) { |

| | pair[0] = "hello!"; |

| | } |

在大多数代码中,元组往往被创建并不被修改,所以在可能的情况下,将类型注释为只读元组是一个很 好的默认。这一点也很重要,因为带有 const 断言的数组字面量将被推断为只读元组类型.

| | let point = [3, 4] as const; |

| | function distanceFromOrigin([x, y]: [number, number]) { |

| | return Math.sqrt(x ** 2 + y ** 2); |

| | } |

| | distanceFromOrigin(point); |

在这里, distanceFromOrigin 从未修改过它的元素,而是期望一个可变的元组。由于 point 的类型被推断为只读的 [3, 4] ,它与 [number, number] 不兼容,因为该类型不能保证 point 的元素不被修改。

TypeScript学习第七章: 类型操纵

7.0 从类型中创建类型

TS的类型系统非常强大, 因为它允许使用其他类型的术语来表达类型.

这个想法的最简单的形式是泛型, 我们实际上有各种各样的类型操作符可以使用. 也可以用我们已经有的值来表达类型.

通过结合各种类型操作符,我们可以用一种简洁、可维护的方式来表达复杂的操作和值. 在本节中,我们将介绍用现有的类型或值来表达一个新类型的方法.

- 泛型型 - 带参数的类型

- Keyof 类型操作符-

keyof操作符创建新类型 - Typeof 类型操作符 - 使用

typeof操作符来创建新的类型 - 索引访问类型 - 使用

Type['a']语法来访问一个类型的子集 - 条件类型 - 在类型系统中像

if语句一样行事的类型 - 映射类型 - 通过映射现有类型中的每个属性来创建类型

- 模板字面量类型 - 通过模板字面字符串改变属性的映射类型

7.1 泛型

软件工程的一个主要部分是建立组件,这些组件不仅有定义明确和一致的API,而且还可以重复使用。能够处理今天的数据和明天的数据的组件将为你建立大型软件系统提供最灵活的能力。

泛型能够创建一个在各种类型上工作的组件,而不是单一的类型。这使得用户可以消费这些组件并使用他们自己的类型。

7.1.1 Hello World

首先, 让我们做一下泛型的"Hello World": 身份函数. 身份函数使用个函数, 他将返回传入的任何内容. 你一用类似于echo命令的方式来考虑它.

如果没有泛型, 我们将不得不给身份函数一个特定的类型.

| | function echo(arg: number): number { |

| | return arg |

| | } |

或者,我们可以用任意类型来描述身份函数:

| | function echo(arg: any): any { |

| | return arg |

| | } |

使用 any 当然是通用的,因为它将使函数接受 arg 类型的任何和所有的类型,但实际上我们在函数返回时失去了关于该类型的信息。如果我们传入一个数字,我们唯一的信息就是任何类型都可以被返回。

相反,我们需要一种方法来捕获参数的类型,以便我们也可以用它来表示返回的内容。在这里,我们将使用一个类型变量,这是一种特殊的变量,对类型而不是数值起作用。

| | function echo<Type>(arg: Type): Type { |

| | return arg |

| | } |

我们现在已经在身份函数中添加了一个类型变量 Type 。这个 Type 允许我们捕获用户提供的类型(例如数字),这样我们就可以在以后使用这些信息。这里,我们再次使用Type作为返回类型。经过检查, 我们现在可以看到参数和返回类型使用的是相同的类型。这使得我们可以将类型信息从函数的一侧输入,然后从另一侧输出。

我们说这个版本的身份函数是通用的,因为它在一系列的类型上工作。与使用任何类型不同的是,它也和第一个使用数字作为参数和返回类型的身份函数一样精确(即,它不会丢失任何信息)。

一旦我们写好了通用身份函数,我们就可以用两种方式之一来调用它。第一种方式是将所有的参数,包括类型参数,都传递给函数:

| | let output = echo<string>("myString") |

这里我们明确地将 Type 设置为 string ,作为函数调用的参数之一,用参数周围的 <> 而不是 () 来表示。

第二种方式可能也是最常见的。这里我们使用类型参数推理——也就是说,我们希望编译器根据我们传入的参数的类型,自动为我们设置 Type 的值。

| | let output = echo("myString") |

注意,我们不必在角括号(<>)中明确地传递类型;编译器只是查看了 "myString "这个值,并将Type设置为其类型。虽然类型参数推断是一个有用的工具,可以使代码更短、更易读,但当编译器不能推断出类型时,你可能需要像我们在前面的例子中那样明确地传入类型参数,这在更复杂的例子中可能发生。

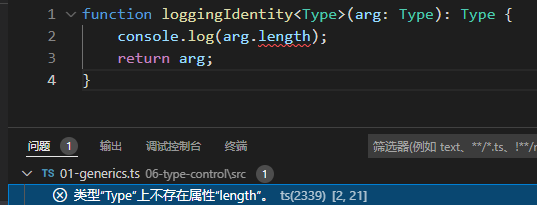

7.1.2 使用通用类型变量

当你开始使用泛型时,你会注意到,当你创建像echo 这样的泛型函数时,编译器会强制要求你在函数主体中正确使用任何泛型参数。也就是说,你实际上是把这些参数当作是任何和所有的类型。

让我们来看看我们前面的echo函数。

| | function echo<Type>(arg: Type): Type { |

| | return arg |

| | } |

如果我们想在每次调用时将参数arg的长度记录到控制台,该怎么办?我们可能很想这样写:

| | function loggingIdentity<Type>(arg: Type): Type { |

| | console.log(arg.length); |

| | return arg; |

| | } |

当我们这样做时,编译器会给我们一个错误,说我们在使用 arg 的 .length 成员,但我们没有说arg 有这个成员。记住,我们在前面说过,这些类型的变量可以代表任何和所有的类型,所以使用这个函数的人可以传入一个 number类型的数字 ,而这个数字没有一个 .length 成员。

比方说,我们实际上是想让这个函数在 Type 的数组上工作,而不是直接在 Type 上工作。既然我们在 处理数组,那么 .length 成员应该是可用的。我们可以像创建其他类型的数组那样来描述它。

| | function loggingIdentity<Type>(arg: Type[]): Type[] { |

| | console.log(arg.length); |

| | return arg; |

| | } |

你可以把 loggingIdentity 的类型理解为 "通用函数 loggingIdentity 接收一个类型参数 Type 和一个参数arg , arg 是一个 Type 数组,并返回一个 Type 数组。" 如果我们传入一个数字数组,我们会得到一个数字数组,因为Type会绑定到数字。这允许我们使用我们的通用类型变量 Type 作为我们正在处理的类型的一部分,而不是整个类型,给我们更大的灵活性。

我们也可以这样来写这个例子:

| | function loggingIdentity<Type>(arg: Array<Type>): Array<Type> { |

| | console.log(arg.length); // 数组有一个.length,所以不会再出错了 |

| | return arg; |

| | } |

你可能已经从其他语言中熟悉了这种类型的风格。在下一节中,我们将介绍如何创建你自己的通用类型,如 Array.

7.1.3 泛型接口

在前几节中,我们创建了在一系列类型上工作的通用身份函数。在这一节中,我们将探讨函数本身的类型以及如何创建通用接口。

泛型函数的类型与非泛型函数的类型一样,类型参数列在前面,与函数声明类似:

| | function identity<Type>(arg: Type): Type { |

| | return arg |

| | } |

| | let myIdentity: <Type>(arg: Type) => Type = identity |

我们也可以为类型中的通用类型参数使用一个不同的名字,只要类型变量的数量和类型变量的使用方式一致。

| | function identity<Type>(arg: Type): Type { |

| | return arg |

| | } |

| | let myIdentity: <Input>(arg: Input) => Input = identity |

我们也可以把泛型写成一个对象字面类型的调用签名。

| | function identity<Type>(arg: Type): Type { |

| | return arg |

| | } |

| | let myIdentity: { <Type>(arg: Type): Type } = identity |

这让我们开始编写我们的第一个泛型接口。让我们把前面例子中的对象字面类型移到一个接口中。

| | interface GenericIdentityFn { |

| | <Type>(arg: Type): Type |

| | } |

| | |

| | function identity<Type>(arg: Type): Type { |

| | return arg; |

| | } |

| | let myIdentity: GenericIdentityFn = identity |

在一个类似的例子中,我们可能想把通用参数移到整个接口的参数上。这可以让我们看到我们的泛型是什么类型(例如, Dictionary 而不是仅仅 Dictionary )。这使得类型参数对接口的所有其他成员可见。

| | interface GenericIdentityFn<Type> { |

| | (arg: Type): Type; |

| | } |

| | |

| | function identity<Type>(arg: Type): Type { |

| | return arg; |

| | } |

| | let myIdentity: GenericIdentityFn<number> = identity |